Between Hôi An and Đà Nẵng are the finest beaches in Vietnam. Waves crash onshore as we walk barefoot upon a stretch of fine sand – we stroll China Beach, where US soldiers went for R & R during the war. The water of the China Sea is warm. Vietnamese call it the East Sea to avoid using the ‘China’ word. I see many unreadable signs, unmistakably propaganda, interspersed with the gentle, smiling face of Ho Chi Minh, particularly around schools.

Passing homes, I look through the front door down a long, narrow hallway and out the back door. Rooms are sparsely furnished with an occasional TV. Homes are generally good in this area and I see numerous tunnel homes – thin, multi-story homes for extended families; plots are small, so they build up. The ground floor is a shop with the kitchen in back and stairs in the middle to living quarters above. Top floor is used for ancestor worship. They don’t waste money decorating the sides as someone will eventually build there. Temperatures are cooler so not only are many motor bikers wearing face masks, but gloves too.

We drive across the lovely Dragon Bridge, so named for its shining gold construction that looks like a dragon. At the bottom of the bridge is the Cham Museum. Records of the Champa Kingdom go as far back as second century AD. At its height in the 9th century, the kingdom controlled the lands between what is now modern Huế, to the northern reaches of the Mekong Delta. Artifacts excavated from their temples are on display, including numerous rock carvings. The Cham decorated their temples with stone reliefs depicting their Hindu gods, such as Shiva and Garuda fighting the Nāga.

We drive across the lovely Dragon Bridge, so named for its shining gold construction that looks like a dragon. At the bottom of the bridge is the Cham Museum. Records of the Champa Kingdom go as far back as second century AD. At its height in the 9th century, the kingdom controlled the lands between what is now modern Huế, to the northern reaches of the Mekong Delta. Artifacts excavated from their temples are on display, including numerous rock carvings. The Cham decorated their temples with stone reliefs depicting their Hindu gods, such as Shiva and Garuda fighting the Nāga.

Hinduism was the predominant religion among the Cham people until the 16th century. (By 1670, the bulk of the population and the Cham royalty itself was Muslim.) Numerous Hindu temples dedicated to Lord Shiva were constructed in the central Việt Nam. The holiest of Cham temples is Mỹ Sơn, often compared with other temple complexes like Angkor Wat. As of 1999, Mỹ Sơn was recognized by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site.

In the 12th century AD, the Cham fought a series of wars with the Angkor Khmer. In 1177, the Cham and their allies attacked and sacked the Khmer Cambodian capital. In 1181, however, they were defeated by the Khmer King Jayavarman VII (builder of Angkor Thom and Bayon). As a result of the rise of the Khmer Empire and Việt Nam’s territorial push to the south, the Champa Kingdom began to shrink. In the 1471 invasion of Champa, it suffered a serious defeat at the hands of the Vietnamese in which 120,000 people were either captured or killed. Just to drive another nail in their coffin, in 1499 The Vietnamese issued orders to kill all Chams within the capital.

When China’s Ming dynasty fell, thousands of Chinese refugees fled south and settled on Cham lands in Việt Nam and Cambodia. Marrying Cham women, their children identified more with Chinese, further weakening Cham culture. Vietnamese expansion ended in the annexation of the Champa Kingdom and their dissolution by the 19th century Vietnamese king, Minh Mạng.

In response, the last Champa Muslim king, Pô Chien, gathered his people and fled south to Cambodia while those along the coast migrated to Malaysia. The Cham community suffered a major blow by Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge, who targeted ethnic minorities like the Cham killing 100,000 of a 250,000 Cham population. Those Cham who remained in central Vietnam were absorbed into Vietnamese society.

In the 1960s various movements emerged calling for the creation of a separate Cham state. However, since the late 1970s, there has been no serious Cham secessionist movement or political activity in Việt Nam or Cambodia.

Today, Cham in Vietnam are officially recognized as one of 54 ethnic groups. Both Hindu and Muslim Chams have experienced religious and ethnic persecution under the current Vietnamese government, with the Vietnamese state confisticating Cham property and forbidding Cham from observing their religious beliefs. Hindu temples were turned into tourist sites against the wishes of the Cham Hindus.

From the Cham Museum we drive to the former Việt Nam capital of Huế (pronounced “way“). Not only is the Cham Empire new to me, so is the history of the 13 Emporers of Vietnam. I will learn about this colorful heritage in the Imperial City of Huế.

Observing the countryside, I see a Buddhist shrine in most every yard. This is a region of mountains, beaches, oyster farming, and scenic bays. Roads are narrow, the centerline viewed as a total nuisance, with the typical endless construction and road bumps. Rice fields are no longer tended with buffalo but with what appears to be a 1900 John Deere mechanization. Bottles of eucalyptus oil line every roadside stand. Bowl boats, used to meet the fishing boats and retrieve fresh fish for markets, are lined up on the beaches. Traffic is slow, motorbikes pass us as do “flying coffins,” the large buses that pass on steep curves. Motorbikes continue to bravely pass on our right. I see more and more bags of trash along the highway. Children, heading home from school, are the first shift of the day; the afternoon shift of children will go to school after lunch.

Serving as Việt Nam’s capital from 1802 – 1945, Huế has traditionally been one of Việt Nam’s cultural and religious centers. Today, Huế is known for its historic monuments, which have earned it a place as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Imperial City occupies a large, walled enclosure on the north side of the Perfume River and is surrounded by a 6 mile moat and 10 gates. Locally known as Dai Noi Citadel, its inner Purple City was based on Beijing’s Forbidden City and reserved for the Nguyễn emperors, concubines, and others close to the Emperor. Punishment for trespassing was death. The Citadel now flys an impressively large Vietnam flag above its fortress walls.

Huế was the capital of the Nguyễn lords, the feudal dynasty who dominated much of southern Việt Nam from the 17th to the 19th century. In 1802, Emperor Gia Long established his control over the whole of Việt Nam, thereby making Huế his national capital. Minh Mạng, reigning from 1820 – 1841 and a younger son of Emperor Gia Long, was well known for his opposition to French involvement in Việt Nam and for his rigid Confucian orthodoxy. But it was Emporer Khai Dinh who became the ‘puppet king’ of the French and his alliance was the beginning of the end for the Emperors of Việt Nam.

When Emperor Bảo Đại abdicated in 1945, a Communist government was established in Hà Nội. While Bảo Đại was briefly proclaimed “Head of State” with the help of the returning French colonialists in 1949 (although not with recognition from the communists or full acceptance of the Vietnamese people), his new capital moved to Sài Gòn.

During the Việt Nam War, Huế’s central location very near the border between the North and South put it in a vulnerable position. In the Tết Offensive of 1968, the city suffered considerable damage due to a combination of American military bombing of historic buildings held by the North Vietnamese, as well as the massacre at Huế committed by the communist forces. After the war’s conclusion, many of the historic features of Huế were neglected because the Nguyễn Dynasty was seen by the Vietnamese Communist Party as “feudal” and “reactionary.”

There has since been a change of policy and historical areas of the city are currently being restored – the mighty tourist dollar at work. The Imperial City, or Dai Noi Citadel with its inner Purple City is sorely in need of a power wash but architecturally stunning with its splendid emperors’ tombs, ancient pagodas and the remains of the Citadel itself.

We finished our day by riding a cyclo to our hotel. Cyclos are three-wheel bicycles with a seat supported by the two front wheels, the driver sitting behind. They are remnants of the French colonial period after a failed attempt to introduce rickshaws. If traffic looked crazed from the bus, on ground level it is insane. Surrounded by motor scooters zipping, cars and buses honking, bicycles peddling, it is a scene of semi-organized chaos. The bigger the vehicle, the bigger the bully. However, the cyclo drivers hold their ground, even when a big red ‘flying coffin’ toots for the right-of-way. Traffic corners were exciting and roundabouts were simply masses of courageous passengers making their way to a stiff drink.

We finished our day by riding a cyclo to our hotel. Cyclos are three-wheel bicycles with a seat supported by the two front wheels, the driver sitting behind. They are remnants of the French colonial period after a failed attempt to introduce rickshaws. If traffic looked crazed from the bus, on ground level it is insane. Surrounded by motor scooters zipping, cars and buses honking, bicycles peddling, it is a scene of semi-organized chaos. The bigger the vehicle, the bigger the bully. However, the cyclo drivers hold their ground, even when a big red ‘flying coffin’ toots for the right-of-way. Traffic corners were exciting and roundabouts were simply masses of courageous passengers making their way to a stiff drink.

Our final morning in Huế begins with a delightful Dragon boat trip on the Perfume River. It is peaceful sharing the waters with bottom dredgers, fishing boats, and smaller Dragon boats, so named for the beautiful dragon heads on their prows. The occasional buffalo or laundress is spotted along the banks.

Tien Mu Pagoda overlooks the river. Its rotund smiling Buddha is a good way to begin our exploration. This active pagoda has some striking carvings and is well maintained.

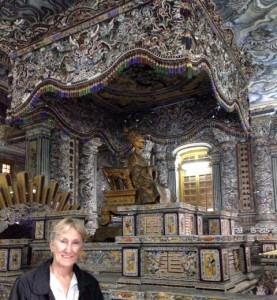

From the pagoda we drive up what must be cemetery mountain as the hillsides are covered in Buddhist family tombs. Toward the crest, with magnificent views, is the tomb of Emperor Khai Dinh, the French ‘puppet king’ who died in 1925. His tomb is gorgeous and ornate; the French supported the Emperor’s efforts to tax the farmers 30% to finance his final resting place. The walls, carvings and decorative work is poured concrete. His likeness sits on a golden thrown beneath an ornate canopy, amid beautifully carved pillars and panels. His person rests below. From this over-the-top ostentation we travel to a second tomb.

The option of fang shui peace and relaxation was chosen by the poetic, but non-militaristic, Emperor Tu Duc, who enjoyed the longest reign of any monarch of the Nguyen dynasty, ruling from 1848-83. Although he had over a hundred wives and concubines, he was unable to father a son. The gardens, his concubines’ quarters, moats and tomb are simple and quiet. He preferred writing poetry than fighting for the independence of his kingdom. His tomb is also memorable because the statues of soldiers are so small as the emperor was short and no one was to be taller in his presence. Tu Duc is not buried in his tomb so as to safeguard his remains from the disgruntled Vietnamese populace. They would rather he had fought.

The option of fang shui peace and relaxation was chosen by the poetic, but non-militaristic, Emperor Tu Duc, who enjoyed the longest reign of any monarch of the Nguyen dynasty, ruling from 1848-83. Although he had over a hundred wives and concubines, he was unable to father a son. The gardens, his concubines’ quarters, moats and tomb are simple and quiet. He preferred writing poetry than fighting for the independence of his kingdom. His tomb is also memorable because the statues of soldiers are so small as the emperor was short and no one was to be taller in his presence. Tu Duc is not buried in his tomb so as to safeguard his remains from the disgruntled Vietnamese populace. They would rather he had fought.

A brief stop allows us to see how the typical Huế palm-leaf conical hat and insense is made. Their pet cat got most of the attention.

A vegetarian lunch was prepared by the Buddhist nuns of Dong Thuyen. There are only 20 left in this hilltop monestary but the grounds, and lunch, are a pleasant change.

It is another flight on the efficiently operated Việt Nam Airlines, this time to Hà Nội. We will be in the heart of the north, hands of the Communist Government, site of Ho Chi Minh’s early victories. The south was good, central Việt Nam better. I expect much of the north.

0 Comments