30 September 2022

Directly across from our Hotel Asia is the magnificent assemblage of architecture known as Lyab-i-Hauz which has survived unchanged since the 16th century. This area once served as a caravansaray along the Silk Road. It includes the Kukeldash Madrassa, Nadir Divan-Beghi Madrassa and the Khanada or lodging house, all centered around Lyabi Khause lake and it’s really big dead tree. The lake is one of the few remaining hauz or ponds remaining in the city. Today it acts as a bustling, hip social venue for locals and a place to see and be seen. Meager food is replaced by large steins of local draft beers and camels and sheep by ducks and cats…the perfect spot on a hot afternoon in which to contemplate the wonderful sights and sounds of Bukhara.

Said Mir Muhammad Alim Khan was the last emir of the Uzbek dynasty. Emir is a military-political-religious leader but while referred to as a king he was not royal. Alim Khan was the last royal male descendant of “legitimate” birth descended from Genghis Khan. He lived much of his early years in St. Petersburg, returning home as a 16-year-old Crown Prince in 1896 (territory was a protectorate of the Russian Empire since 1873). He is forever forward designated by our guide as “that fat strong guy.” The Emir did have a sizable girth.

His Summer Palace was begun by his grandfather and named Sitorai Mokhi-Khosa (Palace of Moon-like Stars) to honor his young wife, who died young. Rumor was the Emir was looking for the best side of Bukhara on which to situate the palace. To say Bukhara is hot in summer would be an understatement. So wise men thought they could determine the coolest region by hanging a slab of meat. Evidently, the meat lasted longer at this site.

Because the palace was built by men trained in Russia, there is a definite mix of east and west architectural styles. I especially liked the use of not only the blue traditional tiles but those of green and a very lovely pink. Each room’s carvings, decorations and artifacts from around Asia are worthy of an Emir. The wandering peacocks add color and big droppings to the gardens.

Alim Khan failed in his efforts to reform the corrupt government. However, he was realistic enough to realize a reformist had little room for Emirs and as a matter of survival, sent the reformist packing to Moscow. Eventually, young activists teamed up with the Bolsheviks and in 1920 the Red Army attacked Bukhara, destroyed the Ark of Kukhara (citadel) and raised their red flag atop the Kalyan Minaret. The Emir wisely got out of town after enjoying this luxury for only 6 years, but not before taking several loads of gold and valuables with him.

Alim Kahn fled to Afghanistan and died in poverty in 1944 in Kabul and is buried there. His daughter worked for Radio Afghanistan before fleeing the Soviet invaders. She and her husband, a journalist, fled to Pakistan and eventually arrived in the Unites States where she joined the Voice of America.

There are many important Islamic complexes around the old city of Bukhara and each is unique. In fact, Bukhara is known as “the city of temples.” It is a miracle any religious site survived the Soviets, who used them for storage or tore them down, and filled in the city’s ponds. It is easy walking form mosque to madrasa to Zaragaron to cafe to restaurant. Bukhara is the perfect wandering, no hassle, people watching city.

We have a short visit to the Chashma-Ayub Mausoleum, referred to as the Well of Job after the prophet’s healing waters. It is unusual because of its pointed tower. The museum explains Bukhara’s water and canal system which once covered this area, most of which is now destroyed or dried up.

The small, simple, wonderfully carved tomb of Ismail Samani is a must-see. Samani was a member of the Islamic Samanid dynasty (819-1005). The tomb’s 10th century brickwork and artistic design reflects strong Persian influences. Religious law of orthodox Sunni Islam strictly prohibits the construction of mausoleums over burial places so the existence of this tomb marks the oldest surviving monument of Islamic architecture. Thankfully, when Genghis Khan invaded and destroyed most of Bukhara, he either failed to notice or ignored the small, unadorned tomb. Sometimes referred to as the “Jewel Box,” the mausoleum would have been a great loss.

The uniqueness of Bolo Hauz Mosque comes from the wonderfully carved wooden pillars of the open pagoda leading to its entrance. Carpets are ready to roll out in preparation for Friday service. The interior is a simple white plaster with bright blue tiles. Built in 1712, it was the mosque of the Emir during the Bolshevik rule in the 1920s. The painted columns are highly decorated and were added to the portal in 1917. Its small minaret was also added at that time.

Ark of Bukhara, a massive 5th century fortification, originally encircled the royal courts and acted as a residence/military headquarters for the Emir. Additionally, it acted as an early military fortress with a circumference of more than 2,600 feet with thick brick walls between 52-66 feet high. This structure is Bukhara’s oldest and historians believe the ancient town of Bukhara arose around this citadel. Over 80% of the fortress was destroyed in the Russian aerial bombings in 1920. What remains is being restored, but only if there are examples to follow. If no tile or design remains of the original, nothing will be done to ornament the walls and ceilings.

The entire enclosed 10-acre area once contained the Emir’s residences, library, harems and more than 3000 people. When Genghis Khan ransacked Bukhara, the inhabitants of the city fled to the Ark, but its walls were not able to repel the invaders and the fortress was ransacked. In 1920, the citadel was bombed by Russian aircraft and the Red Army further damaged the fortress and left the ramparts to deteriorate. The Emir’s 1669 marble thrown, by miracle, was overlooked by the Red Army and remains as an artifact of the last emirs (last crowned here was Alim Khan in 1910). Even so, the brickwork is impressive!

The grand ceremonial entrance is framed by two 18th-century towers which are connected by gallery, rooms, and terraces. A balcony overlooks the main square providing the Emir a prime view of the beheading of the two “British spies” Conolly and Stoddart in 1842, earning the Emir the nickname of “the butcher.” A gentle ramp and stairs lead through a gated portal and a covered hallway to the Dzhuma Mosque. Most of the previous grandeur is gone but one can wander through storerooms and peek into prison cells. In the center of the Ark is a large complex of buildings, one of the best preserved being the Ul’dukhtaron Mosque with some legends about forty girls tortured and cast into its well.

Much restoration is being done but I would be surprised if it is done this century. Restorers only recreate tile and painting if there are patterns to follow. Otherwise, it is left as plain plaster. The “big fat strong guy” had five more palaces but he took most of the wealth of the country with him when he fled the communists.

Nearby, the Kalon Complex on Registan Square consists of the Kalon Mogak-i-Attari Mosque and Kalon Minaret and Kalon Jome Madrassa. The first mosque on this site was built of wood in the 9th century, located atop the remains of a Zoroastrian temple. Destroyed and rebuilt many times, the building, or parts of it, are the oldest surviving structure in Bukhara, even surviving the assaults of Genghis Khan. There was a time, before construction of the first synagogue, when Jews and Muslims shared a place in the mosque. Mostly unadorned, the simple terracotta brick facades are still impressive. The mosque is atypical of others in the city because of its amount of workmanship and artistry. The azure tile domes are gorgeous against a bright blue sky. Ornamentation is mostly carved bricks and tiles with floral motifs. The mosque has sunk over the centuries and is about 14 feet below the surrounding ground. Today, the mosque is utilized as a carpet museum.

The Minaret was erected in 1127 and is also known as the “Tower of Death” because early legend cited criminals thrown off as a form of execution. This seems to be a common legend that is usually denied by the locals, they say it was just good headlines for Russia’s Pravda newspaper. The minaret is taller than most at 150 feet and some historians feel it had multi purposes. The muezzin’s Call to Prayer can be heard throughout the city. The circular-pillar brick tower has 16 windows and a narrow spiral staircase inside. The builder was same man who built the Burana Tower.

It was rumored that Genghis Khan was so impressed by this beautiful tower that he ordered it spared when his men sacked the city. It is no longer used to throw criminals to their death, at least not since 1920 or so.

Each madrasa and mosque is unique, some much more ornate or beautiful than another. However, they are beginning to blur.

It’s in their DNA.

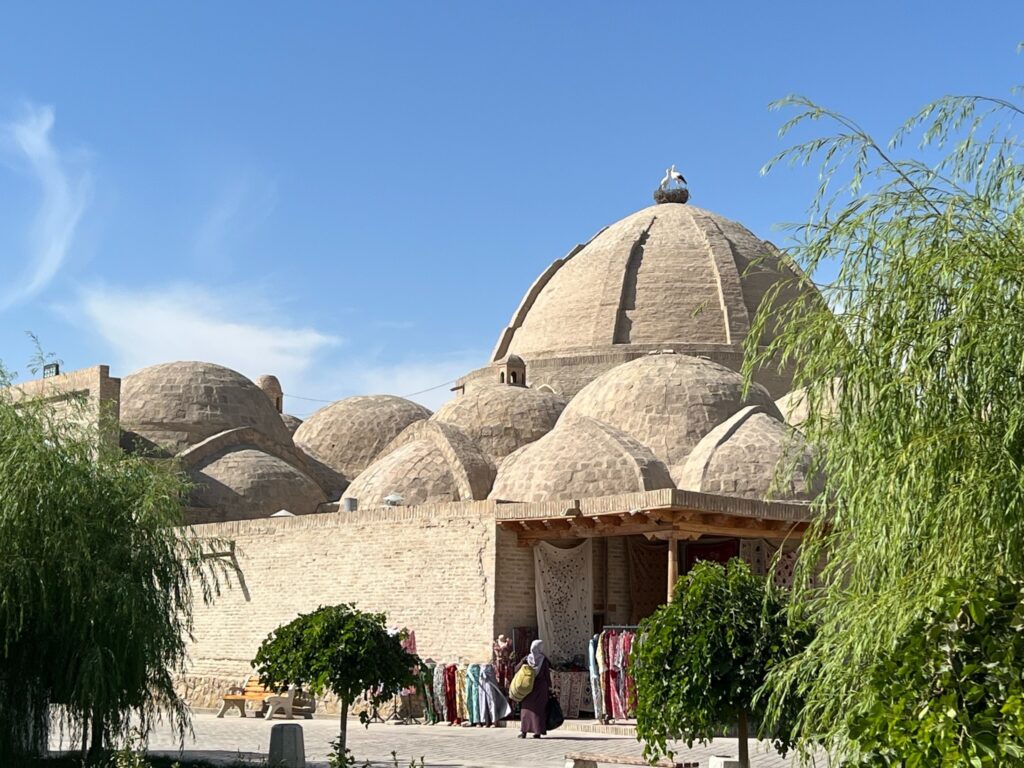

We walk through the numerous Zaragaron, Trading Domes, throughout the old city. Once the city was filled with large “indoor shopping malls” dedicated to meeting any needs of any traveler. These arcades were built at this junction of the Silk Road as a means of controlled and convenient trade. Bartering and selling has always been part of the peoples’ DNA. Expansive open halls beneath eight domes, each Zaragaron had its speciality. Today, the jewelry, hat and money changer domes are all that remain. Displays are attractive; some feature high quality goods, master crafts, musical instruments from quality apricot wood, spices, carpets and silk; others display piles of jewelry, knives, scissors, art, Lenin pins and more table cloths. The one thing absent here is a hard sell. One can actually walk around and admire the goods without too much in-your-face salesmanship. Refreshing!

The Madrassa of Abdul Aziz Khan is an example of the excellent craftsmanship by the Uzbek builders and bricklayers. Built in 1652. The madrasa is colorful and covered with lines of Islamic verse from famous poets. The geometric patterns, use of plant designs and even images of a Chinese dragon and mythical birds makes this building unique. The entry doors have the “dual knocker system” where men and women have separate knockers. This allowed to woman to know which sex was at the door as she was not to open for a man. Marble carvings, tile and brick mosaics, wall paintings and gold gilding decorate the interior. Opposite is the second of Madrasas built by Ulugbek (first was the one built in Samarqand). This school is active.

The Kukeldash Madrassa (1568) was the largest in the city and has a simpler but tiled and brick façade. Built on the early site of a Zoastrian temple, it has suffered the same fate as many madrasas, previously being used to sell carpets and now being renovated. It is surrounded my an ancient caravansaray which was recently partially unearthed.

On the west end of the Lyabi Hovuz Park complex is Nadir Divan-Beghi Madrasa (1623) representing the Janid dynasty (1599) which followed the time of the khans. The Janids were thought to be less traditional than the khans and introduced richer colors and artistic expression. The exterior of this religious school is impressive, its portal decorated with two phoenix, two white deer and a sun face.

Divan-Beghi Khanaka (1620) on the eastern side of Lyabi Hovuz is a rectangular building topped with a plain dome. A khanaka is designed specifically for retreats for Sufi itinerant travelers. This is a rather plain building with a bit of floral ornamentation and two squat towers on either side of the main portal.

However, the peace d’resistance of Lyabi Hovuz is the Divan Beghi pool now home to ducks and friendly cats . It is the perfect spot for a cold draft of Sarbast, a local beer (think Uzbekistan Carlsberg). Sit and the kittens will come, some so sweet I want to take them home. Cats are treated well and diners make sure they get their meals; however, there is no neutering programs which is a shame.

Nearby is the wonderful bronze sculpture of Khoja Nasruddin atop his faithful donkey. Nasruddin, born in Bukhara, traveled the Silk Road dispensing his wisdom and humor. Evidently he Liked to punish greedy people. The story goes that some poor dervishes were being hassled to pay for a BBQ that they hadn’t eaten. The cook said they had enjoyed the smell while sitting in the square for two hours and should pay. Nasruddin came to the rescue and offered to pay for the smoke. “Jiggling his purse he asked “Hear the sound of coins that paid for pleasant smoke?”

Enjoying an evening refreshment around Divan Beghi pool with the kitties coming by to say good night, I think of Nasruddin atop his donkey. I am sure he was a great spokesman for why travelers should stop in his hometown. I doubt if any traveler was ever disappointed. Unless of course, he was tossed from the Tower of Death.

0 Comments