2 October 2022

Ichan-Qаl’а is the walled inner town of the city of Khiva. In 1990, it was recognized as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. A day visiting its sites, wandering its narrow streets and squares, and walking its walled fortifications clearly proves why it has earned that honored designation.

Early morning finds me at West Gate, one of four gated entries into the walled city. Ichan-Qаl’а, even with its multitudes of Uzbek salespersons, is an easy city to explore.

Khiva is the oldest recognized UNESCO World Heritage Site in Uzbekistan. Historically, it is like walking back several centuries in time to when the Silk Road and its travelers stopped at this caravansaray for rest and refreshment before departing along the dry, barren route into Persia. Founded at least 2500 years ago, Khiva’s name is attributed to Shem, a son of Prophet Noah. After the flood and some wandering in the desert, Shem is said to have experienced an omen telling him to found a city here. Shem dug a well, which still exists in the walled city. Another story, less biblical, is that the city got its name when travelers drank the excellent water from the well and exclaimed “Khey vakh!” meaning “What a Pleasure!” Either story is more colorful than the city getting its name from an abbreviated Turkic word.

Either way Khiva was named, for centuries it has stood and flourished at this crossroads of Central Asia. The actual city is two parts: an inner town located within its ancient walls known as Ichan-Qаl’а and an outer town outside the walls called Dichan-Qаl’а.

Ichan-Qаl’а is surrounded by foundations laid before the 10th century. Its 33-foot crenellated mud and brick walls only date to the late 1600s but create a formidable challenge for any invaders. Along its narrow alleys are a plethora of historic houses, mosques, madrassas, minarets, bazaars, and monuments. Entering one of its city gates is like walking back in time when the caravans, khans, traders and maybe even Shem walked these streets.

Easily noticeable is Kalta Minor, or “short minaret,” begun by Mohammed Amin Khan in 1851 but never finished by his successors after his death. Only rising about 92’ it is still one of the most memorable towers in the city. This gorgeous minaret is completely covered with sparkling glazed tiles. Its flat top is a clear indication that it was never completed. It really is more of a cylinder tower and not nearly as high as the Khan had planned, hoping it could be seen “all the way to Bukhara.” Other minarets may be taller but there are few in all of Uzbekistan that are as beautiful.

We stop at the Prison Museum where “Guardians of Sharia law in Khiva” practiced such ingenious tortures as stoning, live burials, impaling, and throwing people down from towers. Unfaithful women were tied into a sack of cats and beaten. It was the Russians who banned the slave market in the 1860s and also put a stop to the more barbaric methods of punishment.

I notice that Uzbeks want to deny people were thrown from towers or often say unpleasant facts may have been the result of Russian propaganda. I’m not so sure. It has been over 30 years for researchers and historians to correct any incorrect messaging. This reminds me of the Romans denying the coliseum was used for Christians and lions.

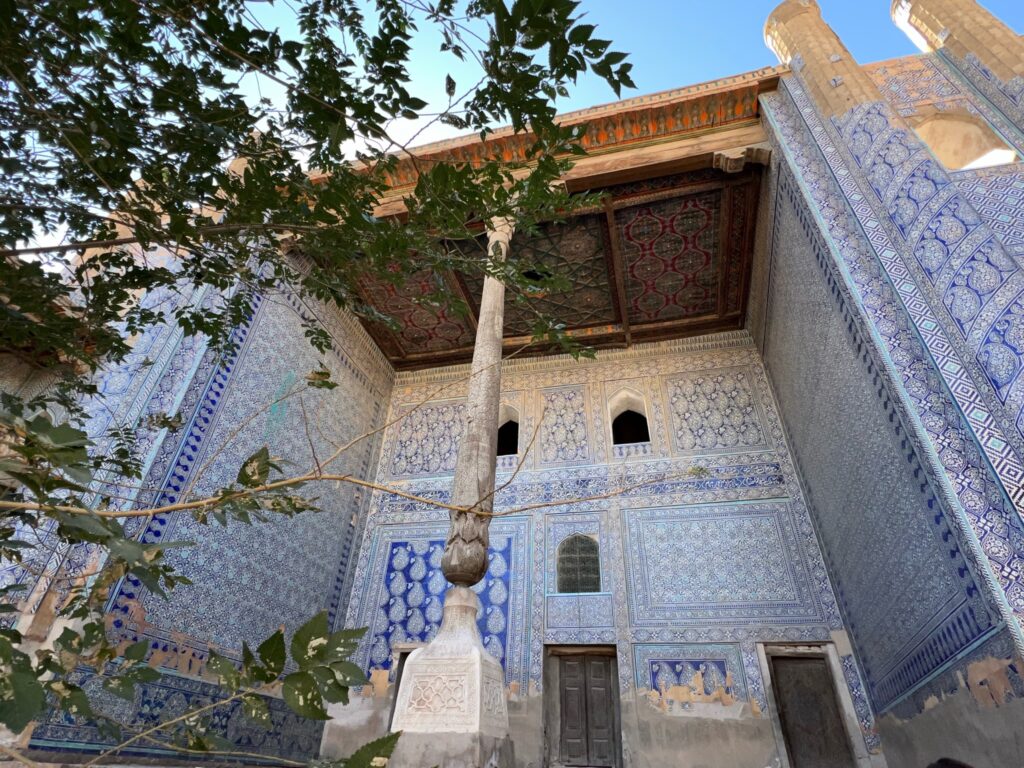

Kunya Ark Citadel was begun by the Khan in 1686. The large walled complex lies along the western wall of the town and contains several courtyards surrounded by what was the Khan’s residence, guest rooms, kitchens, stable and harem, only a few of which have survived. The slim corner towers are artfully decorated at the top with wonderful aquamarine glazed tiles. The interior tiling is superb; entire galleries are covered with majolica glazed blue and white tiles.

In one courtyard can be seen the “doors of justice.” Here, the khans were swift to punish with decisions taking only a few minutes. Your fate was determined by the door you used to exit. One was for the not guilty, one led to prison, the middle led to death. In the middle of the courtyard, the round, raised platform was for the Khan’s summer yurt. This would be no simple tent but as luxurious as it’s surroundings. The large pagoda, shining with blue tiling, prepares you for the bling within. Ceilings, mostly of carved and painted wood, carved elm pillars, tiled walls, floors and every niche are exquisite.

The museum here has an interesting exhibit about Uzbekistan money. There is a 200,000 bill, worth about $18. One would need a wheelbarrow to be paid in cash. When Soviets were here they had their own “funny money” of coupons. To avoid forgeries, all color printers had to be registered with the KGB.

I admit that the architecture is beginning to blur. Another mosque, madrassa, a minaret here there and everywhere. A memory exercise I like to perform after days on the road is trying to remember my former room numbers. After 18 days, I find remembering the cities and hotels is enough of an achievement.

The Mohammed Rakhim Khan Madrassa was ordered by the Khan in 1871 just before the Russians arrived in 1873. Trying to appease both Islamic tradition and the Russians, the madrassa was a little more secular and included science, math and astronomy. The school is arranged around a courtyard. The brick façade and round-domed twin towers are decorated with glazed tiles of floral and geometric design. Showing a bit of wear, the madrasa now hosts a museum on the Rakhim Khan and the khanate. Khan II brought stability of progress but was murdered in 1910; his son took over but avoided the Russians by fleeing to Ukraine where he died. On 2 February 1920, the red communist flag was raised above the Citadel.

Something that does not change is the salespeople, mostly women. Each nook and cranny, all courtyards and many rooms contain a shopping opportunity, not as aggressive as Samarqand but pushier than Bukhara, the goods range from pashminas to heavy knitted socks and fur hats. They are still selling travel books. In one courtyard we are given a demonstration by a master wood carver, carving multi-position book stands and boxes from one piece of elm or maple. He shows how to set one up in several positions, all of which I would never figure out once I got home.

The Pakhlavan Makhmoud Mausoleum, also within the protective walls of Ichan-Qаl’а, is stunning. Its simple brick exterior is deceiving. A magnificent green dome of Timurid-blue towers above the central chamber. The building is quite large and houses the tombs of several khans. However, the overall mausoleum is named for Pakhlavan Mahmoud, honored Iranian poet and wrestler who lived to the age of 79, dying in 1326 and entombed here with the Khan I and members of his family. Pakhlavan was not only a great literary and athletic giant, but a chivalrous one. The interior of the mausoleum is very ornate with intricately designed glazed tiles with gold overtones. The ceilings are magnificent.

The Islam Kjoha Madrassa and minaret was the last one built in Khiva by a man of the same name. He was good for the city but he too was murdered in what they thought was a revenge killing as his head was never found. The elm doors are unique, individually carved works of art. I’m told the Madrassa is inactive.

The Juma Mosque, or Friday Mosque, is unique because of its interior of 213 carved wooden pillars of black elm. Operating since 1788, it is a gigantic open-air rectangle of about 8800 square feet. Even though part of the ceiling is open, there are no windows and the interior is somber. The oldest pillars are from the 10th century while several others are from the 18th century; remaining pillars were added over 8 centuries of time. The pillar’s decorative carving depends on what century they were carved. Its beautifully tiled minaret is 108 feet tall.

Toshhovli Palace, or Stone House, is certainly more than its name indicates. Within its walls is a very decorated interior. Built by Alakuli Kahn starting in 1832, it is meant to impress his visitors. Unfortunately, he was a man with little patience and when his first architect, Tosh-Hovli, was taking too long the khan had him killed. In spite of this irritation in construction, the palace was completed by 1841. The palace contains a maze of 150 rooms, 9 courtyards, large harem housing 30-50 women usually imported for ethnic variety, throne room and sumptuous covered portico (avian). His high-bling yurt is set up in the courtyard. There is also a handicraft museum in one section. The high ceilings, tiled walls, carved pillars and ceilings, and priceless carpets are impressive. The khan was repaid for his impatience and today his palace bears the name of his executed architect.

After lunch, I stroll through the quiet back streets. There are no salespeople, no cars, no hassle. Finding the North Gate, I climbed the steps to the top of the 33-foot fortifications for a wonderful vista of the town. I soon come upon a large group of men in the road below. Cars parked every which way, music blasting, men enthusiastically dance in the street. Perhaps a block away are the women, more sedate, piling carpets into the back of a car. Many cars leave with much honking, meeting the men in the street who rush to their cars to join the honking celebration. I don’t see a bride so could be a wedding or funeral, don’t know. Around me are the minarets and sparkling domes of Ichan-Qаl’а. An Uzbekistan scene on a Sunday afternoon.

My day around the Ichan-Qаl’а has been amazing. One could spend much more time wandering its alleys and the assortment of buildings. But, it is time to enjoy a refreshing Uzbek beer. A nice pale Sarbast is an inexpensive 30,000 Soum, about $2.60. Still no straws served. Perhaps western ways of drinking beer have arrived.

0 Comments