16 September 2016

Today I am driven south through “rustic” scenes of drying corn fields, herds of sheep, flocks of turkeys, women working fields with large wooden rakes, simple villages, minarets, horse carts and pack donkeys, clearly a simple “peasant” life of a rural Albania. I see more women in traditional clothing but the homes are mostly modern and large. More roadside police are seen. I also see people driving on the right side of the car.

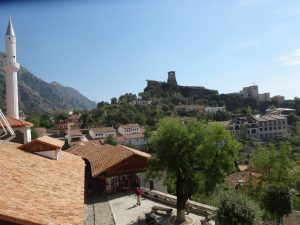

Lezhë is extremely important to the people of Albania. Our destination is the Memorial to Skanderbeg. High over town is the ubiquitous fortress. But it is for Skanderbeg we come – Albania’s “Alexander.” I have read of Alexander the Great, Napoleon, Genghis Khan and Hannibal. However, unknown to me was the great military commander known as Skanderbeg. He faced unbelievable odds yet despite the adversity, he prevailed. (I thank Wikipedia, local literature and information for filling in my lack of education about one of the greatest general’s of all time. Omission and errors are mine.) I start at his memorial, below the ancient fortress.

Skanderbeg (Gjergj Kastrioti 1405-1468) was an Albanian nobleman and military commander who served the Ottoman Empire in 1423–43, the Republic of Venice in 1443–47, and lastly the Kingdom of Naples until his death. After leaving Ottoman service, he led a crusade for independence of Albania from Ottoman rule.

A member of the noble Kastrioti family, he was sent as a political hostage to the Ottoman court, and conscripted into the Devşirme system, a military institute that enrolled Christian boys, converted them to Islam, and trained them to become military officers for the Sultan. Thus the Sultan would exercise control in the area of the father. The treatment of the hostage was not a bad one: sons would be sent to the best military schools and trained to be military leaders.

Skanderbeg participated in Ottoman military campaigns against Christians until 1443, when he deserted the Ottomans during the Battle of Niš and immediately led his men to Krujë Northern Albania and by the use of a forged letter from Sultan Murad to the Governor of Krujë he became lord of the city. Legend says he raised a red standard with a black Byzantine double-headed eagle over Krujë (Albania uses a similar flag to this day). Skanderbeg reconverted to Christianity and ordered others who had embraced Islam to convert to Christianity or face death.

Skanderbeg participated in Ottoman military campaigns against Christians until 1443, when he deserted the Ottomans during the Battle of Niš and immediately led his men to Krujë Northern Albania and by the use of a forged letter from Sultan Murad to the Governor of Krujë he became lord of the city. Legend says he raised a red standard with a black Byzantine double-headed eagle over Krujë (Albania uses a similar flag to this day). Skanderbeg reconverted to Christianity and ordered others who had embraced Islam to convert to Christianity or face death.

In 1444, he became chief commander of the League of Lezhë thus consolidating nobility throughout Albania. With partisan support, Skanderbeg organized a mobile defense army that used hit-and-run tactics of a guerrilla war against the Ottomans and used the mountainous terrain to his advantage. During the first 8–10 years, Skanderbeg commanded an army of generally 10,000-15,000 soldiers.

Despite his military valor he was restricted to a small area in northern Albania where almost all of his victories against the Ottomans took place. Skanderbeg’s rebellion was not a general uprising of Albanians, as he did not gain support in the Ottoman-controlled south or Venetian-controlled north. For 25 years, from 1443 to 1468, Skanderbeg’s 10,000 man army marched through Ottoman territory winning against consistently larger and better supplied Ottoman forces.

In 1460–61, he participated in Italy’s civil wars in support of Ferdinand I of Naples. In 1463, he became the chief commander of the crusading forces of Pope Pius II, though that Pope died while the armies were still gathering. But he fought anyway. Together with Venetians he fought against the Ottomans during the Ottoman–Venetian War (1463–79) until his death in January 1468.

Skanderbeg’s military skills presented a major obstacle to Ottoman expansion, and he was considered by many in western Europe (along with his contemporaries Vlad III Dracula in Wallachia and Stephen III the Great of Moldavia) to be a model of Christian resistance against the Ottoman Muslims. Before his return to Christianity, Ottoman Turks called him Iskender bey, meaning “Leader Alexander,” assuming a comparison of Skanderbeg’s military skill to that of Alexander the Great. After his desertion he was referred to as “kh’ain (treacherous) Iskender.”

After his split from the Ottoman Empire, Skanderbeg led successful after successful campaign against the Ottomans. In 1444, Skanderbeg’s Albanian armies of 18,000 men faced General Ali Pasha’s army of 25,000 men which gave Skanderbeg his first victory. This was one of the few times an Ottoman army was defeated in a pitched battle on European soil. (I will visit Ali Pasha’s spectacular fortress further south in Gjirokestrë.)

At first, Skanderbeg’s Albanian insurrection seemed a good thing to the Venetians. However, his rise as a strong force on their borders came to be seen as a threat, starting the Albanian-Venetian War in 1447. The Venetians sought by every means to overthrow Skanderbeg or bring about his death, even offering a life pension of 100 golden ducats annually for the person who would kill him. During the conflict, Venice invited the Ottomans to attack Skanderbeg simultaneously from the east, facing the Albanians with a two-front conflict. Skanderbeg learned of the treachery and in 1448 he crossed the Drin River with 10,000 men, meeting a Venetian force of 15,000 men. He ordered a full-scale offensive, routing the entire Venetian army. A lucrative peace treaty was signed between Skanderbeg and Venice on 4 October 1448. Then Skanderbeg intensified relations with Alfonso V of Aragon (r. 1416–1458), who was the main rival of Venice in the Adriatic, where his dreams for an empire were always opposed by the Venetians.

In 1450, Ottomans laid siege to Krujë with an army numbering approximately 100,000 men and led again by Sultan Murad II and his son, Mehmed II. Following a scorched earth strategy, Skanderbeg left a protective garrison and with the remainder of the army, which included many Slavs, Germans, Frenchmen and Italians, he harassed the Ottoman camps around Krujë. The garrison repelled three major direct assaults on the city walls by the Ottomans, causing great losses to the besieging forces.

Over the next years, the Ottomans laid siege to the garrison at Krujë three times. Murad II, and later his son Mehmed II, ultimately acknowledged they could not capture the castle of Krujë by force of arms. But the nobles from the region rejected Skanderbeg’s efforts to enforce his authority over their domains, yet he held Krujë and regained much of his territory.

In a second attack five years later, Skanderbeg’s victory over a ruler even more powerful than Murad came as a great surprise to the Albanians. In 1453, Mehmed sent another expedition to Albania and Skanderbeg launched a swift cavalry attack which broke into the enemy camp causing disorder and chaos. The Siege of Berat in 1454 was the first real test between the armies of the new sultan and Skanderbeg.

The Ottomans did not give up. In the summer of 1457, an Ottoman army numbering approximately 70,000 men invaded Albania with the hope of destroying Albanian resistance once and for all. After having avoided the enemy for months, calmly giving to the Ottomans and his European neighbors the impression that he was defeated, on 2 September Skanderbeg attacked the Ottomans in their encampments and defeated them killing 15,000, capturing 15,000 and 24 standards, and all the riches in the camp. This was one of the most famous victories of Skanderbeg over the Ottomans, which led to a five-year peace treaty with Sultan Mehmed II.

In November 1463, Pope Pius II tried to organize a new crusade against the Ottomans, similar to what Pope Nicholas V and Pope Calixtus III tried before. Pius II invited all Christian nobility to join, and the Venetians immediately answered the appeal. So did Skanderbeg, who on 27 November 1463 declared war on the Ottomans and attacked their forces near Ohrid. Pius II’s planned crusade envisioned assembling 20,000 soldiers in Taranto, while another 20,000 would be gathered by Skanderbeg. However, Pius II died in August 1464, at the crucial moment, and Skanderbeg was again left alone facing the Ottomans.

Nothing if not persistent, in 1466, Sultan Mehmed II personally led an army of 30,000 into Albania and laid the Second Siege of Krujë, as his father had attempted 16 years earlier. The town was defended by a garrison of 4,400 men. After several months of siege, destruction and killings all over the country, Mehmed II, like his father, saw that seizing Krujë was impossible for him to accomplish by force of arms. Subsequently, he left the siege to return to Constantinople.

Skanderbeg spent the following winter of 1466–67 in Italy, of which several weeks were spent in Rome trying to persuade Pope Paul II to give him money. At one point, he was unable to pay for his hotel bill, and he commented bitterly that he should be fighting against the Church rather than the Ottomans. It is possible that the Curia only provided to Skanderbeg 20,000 ducats in all, which could have paid the wages of 20 men over the whole period of conflict. Skanderbeg probably financed and equipped his troops from local resources, richly supplemented by Ottoman booty.

On his return to Albania on 23 April 1467, Skanderbeg attacked the Ottoman forces laying siege to Krujë. The Second Siege of Krujë was eventually broken and the Ottomans offered to surrender all that was within the camp to the Albanians. Skanderbeg was prepared to accept, but many nobles refused. The Albanians thus began to annihilate the surrounded Ottoman army On 23 April 1467, Skanderbeg entered Krujë. The victory was well received among the Albanians.

Mehmed II again marched against Skanderbeg in the summer of 1467. Skanderbeg retreated to the mountains. The Ottomans failed again in their third Siege of Krujë, both to take the city or to subjugate the country, but the degree of destruction was immense. During the Ottoman incursions, the Albanians suffered a great number of casualties, especially to the civilian population, while the economy of the country was in ruins.

In January of 1468, here in Lezhë, probably close to where I stand at this Monument to Skanderbeg, this great military leader called together all the remaining Albanian noblemen to a conference in this Venetian stronghold to discuss a new war strategy and to restructure what remained from the League of Lezhë. During that period, Skanderbeg fell ill with malaria and died on 17 January 1468, aged 62.

The Albanian resistance to the Ottoman invasion continued after Skanderbeg’s death, led by his son, Gjon Kastrioti II, who tried to liberate Albanian territories from Ottoman rule.

The Ottoman Empire’s expansion ground to a halt during the time that Skanderbeg’s forces resisted. He has been credited with being one of the main reasons for the delay of Ottoman expansion into Western Europe. His main legacy was the inspiration he gave to all those who saw in him a symbol of the struggle of Christendom against the Ottoman Empire. During the Albanian National Awakening Skanderbeg was a symbol of national cohesion and cultural affinity with Europe. Skanderbeg’s struggle against the Ottomans became highly significant to the Albanian people. It strengthened their solidarity, made them more conscious of their identity, and was a source of inspiration in their struggle for national unity, freedom, and independence.

The trouble Skanderbeg gave the Ottoman Empire’s military forces was such that when the Ottomans found the grave of Skanderbeg in the church of St. Nicholas in Lezhë, they opened it and made amulets of his bones, believing that these would confer bravery on the wearer. Indeed, the damage inflicted to the Ottoman Army was such that Skanderbeg is said to have slain three thousand Ottomans with his own hand during his campaigns. Among stories told about him was that he never slept more than five hours at night and could cut two men asunder with a single stroke of his scimitar, cut through iron helmets, kill a wild boar with a single stroke, and cleave the head of a buffalo with another. Certainly the statues of him reflect an imposing giant of great strength and fortitude.

The Italian baroque composer Antonio Vivaldi composed an opera entitled “Scanderbeg” and on October 27, 2005, the United States Congress issued a resolution “honoring the 600th anniversary of the birth of Gjergj Kastrioti (Scanderbeg), statesman, diplomat, and military genius, for his role in saving Western Europe from Ottoman occupation.”

The Memorial to Skanderbeg is a simple columned building but of immense importance to Albania. The shields along the walls commerate his victorious battles. The red tile, double-headed eagle mosaic depicts his flag and that of Albania. The stone tablet with sword and famous horned helmet grace where Skanderbeg rests. His history and military skill speaks for itself.

We continue to explore this one-time stronghold of Skanderbeg and visit the hill town of Krujë. It is quite a climb even for the vans, steep, cobbled and narrow, better suited for donkeys than horsepower. I browse the shops at the foot of the castle. It has the feel of a Turkish bazaar but without the “kidnapping” to get you into their shop. I find a nice man with lots of military and communist pins and he is delighted to show me his selection. The group lunches overlooking the fortress hill, even higher and more inaccessible.

Atop the fortress, we are shown around another Ethnographic Museum, much the same as the other Turkish house we have seen. Tradesmen’s shops are below demonstrating oil presses, weaving, butter and cheese making, iron forging. Upstairs, the family lives, many generations with the man of the house making sure the women follow what is expected of them. There are separate rooms designated for children, women, men and the guest. And the richer the family, the more fire places. The rooms are open and airy, simple and comfortable.

But the star attraction of this fortress/castle is the Museum of Skanderbeg. The fortress surrounds me and is the remains of the fortress that Murad II and son Mehmed II tried three times to take, failing each time because of Skanderbeg’s armies. It was here that Skanderbeg first raised his red standard with a black Byzantine double-headed eagle, probably the precursor of Albania’s modern flag. (The second flag seen most often in Northern Albania is the American flag.)

One of Skanderbeg’s most important speeches was given here:

“I haven’t gave you the freedom, but I found it among you.”

The Museum of Skanderbeg is excellent, though not in English. In several rooms, the life and military victories of Skanderbeg are detailed. It could only be improved by translating the information into English.

I end my day with tremendous respect for this soldier and leader. Indeed, Skanderbeg does deserve to rank up there as one of the top ten generals of all time.

0 Comments