29 September 2025

This morning, we begin our days of train travel. For someone from the U.S., I am always impressed by the development and efficiency of public transportation around the world. In most of my country, without a car, you’re screwed. There exist few reliable public transportation options. Therefore, while the Japanese may apologize and fret about a train being a minute late, I am just happy it shows up and gets me where I want to go.

Because we ride trains for much of our future transport, arrangements were made to transfer luggage by van. They ship our bags to our destination two days hence. For me, absolutely no problem. I travel light. With my day pack, I carry about 17 lbs. Admittedly, a pound or two of that consists of electronics. My shoes retrieved from the ryokan, I’m ready to go.

Matsumoto Castle

Matsumoto, originally Fukashi Castle, and known as the Crow Castle for its striking lack exterior, represents one of Japan’s most beautiful and historic castles.

Built in the 16th century, the keep maintains its original external stonework and wooden interiors. Designated as a National Treasure of Japan, the keep remains one of the most complete among Japan’s twelve surviving castles.

Unlike many other castles built on hilltops, Matsumoto, a hirajiro, sits on flatland, strategically designed with an intricate system of moats, walls, and gatehouses for defense. Construction began during the Sengoku, or Warring States period, when powerful warlords fortified their domains.

Six levels, completed around 1594 under the rule of the Ishikawa clan, hide within five stories of the main keep (tenshu). Remarkably, the castle survived wars, earthquakes, and modernization, making it a rare surviving example of original Japanese castle architecture.

The interior feels like stepping back into the era of samurai, with very steep wooden stairways, dark timber beams, and openings once used for archers and gunmen. The second floor of the main keep features a gun museum, a Teppo Gura, with a collection of guns, armor, and other weapons. From the top, one enjoys sweeping views of the Japanese Alps, a dramatic backdrop that highlights the castle’s formidable past.

The castle weathered many storms over four hundred years. In 1872, the new Meiji government ordered the destruction of all former feudal fortifications. Developers razed most of the castle structures and sold the outer grounds of Matsumoto Castle at auction for redevelopment. Thankfully, local residents rescued the castle, and the city government acquired it. Since then, the castle has withstood age, decay, neglect, and even a 5.4 earthquake in 2011. Its designation as a National Historic Site and National Treasure now guarantees its survival.

Mad About Miso

First confronted with miso in my pantry, purchased by my niece, I wondered what it was and what could I do with it. A pasty mixture of fermented soybeans, salt, and koji (a type of mold culture made from a grain like rice or barley or soybeans), isn’t exactly tempting. Reaching for my iPad and Google Search, I expanded my culinary horizons.

Miso is a Japanese seasoning paste known for its salty, umami-rich savory flavor. Sort of a fifth element of taste. I read that it deepens the flavor of dressings, sauces and soaps. I generally enjoy Asian food and especially the soups. Since, miso has become a staple in my pantry.

We tour the Ishii Miso factory to learn about the history and production of this vital staple to Asian cooking. Miso originated over 1300 years ago, probably in China. In the beginning, the savory paste likely derived from seafood or meat.

The owner assures us that his miso is the best in Japan, fermented in cedar vats. The darker the color the stronger and better his miso. They do not export. Even here the sales pitch starts early. Surprisingly, we eat lunch and shop later. Even more surprising, costs seem pretty reasonable, if one desires to carry a jar of miso home.

Today, miso is plant-based. Depending on the ratio of ingredients, type of grain used and length of fermentation, miso can run the gamut from sweet, light and mild to earthy and nutty to rich, bold and intense. The darker the miso, generally the bolder the flavor.

After our tour, we dine on a huge miso-based lunch. Though high in sodium, basically miso is healthy and nutritional. They tell me it is good for one’s immune system, blood clotting, brain-building and linked to longevity.

Ubiquitous prop for ice cream – except this one is with miso!

Luckily, I’m good for the sodium. As for the rest of miso’s assets, I am happy just to enjoy the delicious flavor it adds to foods. However, I passed on the miso ice cream – just something wrong about that.

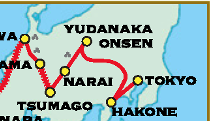

Kiso Valley via Train

After lunch, we continue by train crossing and recrossing the highway, river, along ravines and through dense forests. Spectacular views of forested mountain peaks line both sides of the train as we zoom on our way southwest. Small villages pass by. We enter the occasional quiet little station. I try to read the cost of gas as we pass but prices quoted in Japanese. Possibly a little more than a dollar a liter.

We ride the Local JR Shinonoi & Chuo Line. Local trains are a world apart from the sleek Shinkansen high-speeds. Instead of futuristic bullet shapes and uniformed attendants bowing, you get modest two-to-four-car trains painted in cheerful colors, often with big windows.

The pace is unhurried—sometimes very unhurried, as these trains may stop at every town, hamlet, and vending machine.

Inside, the seats are bench-style, covered in sturdy fabric that has survived generations of uniformed school kids, farmers with baskets or maybe a chicken, and grandmothers carrying shopping bags. Locals hop on and off with practiced ease. The announcements come in rapid-fire Japanese and English. These rides aren’t about speed; they’re about enjoying the rhythm of daily Japanese life, where the journey itself is the attraction.

Nakasendō Way

The Nakasendō Way, a historic Japanese pilgrimage route and one of the five major Gokaido (routes) built during the Edo period (1603-1867), connected the former imperial capital of Kyoto to Edo (modern-day Tokyo). Ths 332-mile long mountain path, known for its well-preserved post towns (juku) and scenic natural landscapes, make it popular with hikers.

The road acted as a crucial trade and travel route during the Edo period, frequented by daimyos (feudal lords), merchants, and travelers The route features numerous preserved post towns, such as Magome-juku and Tsumago-juku, which offer a glimpse into life centuries ago. Many museums and points of interest lie along the route.

In the Kiso Valley, along the Nakasendō Way, sits the charming village of Narai-juku.

Overnight in Narai-juku

Narai reeks of traditional. Located directly along the ancient Nakasendō Way between Kyoto and Tokyo, it contains a wealth of well-preserved wooden houses and former inns. Often called Narai of a Thousand Houses, it represents one of the best-preserved post towns along the Nakasendō. Walking its single, mile-long street feels like stepping straight into the 17th century—without the risk of running into a feudal lord’s entourage or samurai sword.

Tall, dark wooden houses line both sides of the road, their latticed windows and deep eaves perfectly preserved. Many now hold family-run shops, inns, and little tea houses that have served weary travelers for centuries.

Narai isn’t flashy and that’s exactly its charm: a living museum of the old road, where the echoes of past travelers and new tourists bounce along the timbered walls.

Browse lacquerware, Narai’s specialty, or sip tea in a café. Being very traditional though, I haven’t stumbled across a wine bar. This is more a town for tea, lacquerware, and Edo-period vibes than sipping Chardonnay. That said, I’m not doomed to a tea-only existence. We lodge here for the night and the inns do have a small selection of beer, saké, or the occasional glass of wine tucked behind the counter.

Lodging at the Iseya

Surrounded by beautiful mountains, our lodging is the Iseya, a lovely traditional inn founded in 1818.

The architecture is stunning with an overhanging second floor of rooms (dashibari-zukuri) and windows decorated with fine wooden lattice work (senbon-koshi).

Some rooms were built more than 200 years ago while the annex appears more modern. However, both areas are old wooden buildings with fusuma doors (fusuma are vertical rectangular panels which can slide from side to side). Bathrooms and toilets are shared.

Public bath. All toilets and baths down the hall. Always separate.

No street shoes beyond Lobby. Slippers for going to the room. Bare feet in room. Separate slippers for the toilet. Slippers to dining then bare feet or socks again.

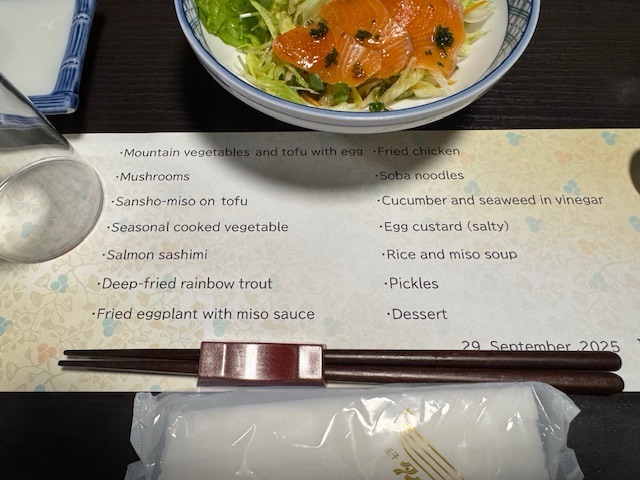

But this novice can’t distinguish between egg custard and tofu. If it tastes good, eat it. The trout, salmon and salad were delicious. Terrific salad dressing.

One adjusts to the Japanese life. That seems hard for a spoiled American. But the lovely grounds and rooms, tasty dinner with a chilled glass of saké, and the culture and people could not be more charming. Japanese culture appears to offer several concepts that embody different facets of a rich and purposeful life. These philosophies encourage finding daily joy, appreciating imperfection, and having a purpose for getting out of bed each morning.

The phrase Ichigo ichie best describes it: be present and appreciate every unique moment.

0 Comments