1 October 2025

A short drive takes us southerly over the 2,628-foot Magome Pass. The pass is the highest elevation along the Nakasendō Way. Surrounding mountains and the cedar and bamboo forests are outstanding. It is difficult to consider these undulating hills as mountains when I regularly drive over passes at 4,000’. However, unlike the more northern peaks in Japan that can receive up to 50 feet of snow, the Tsumago-Magome area is more temperate and snowfall is not as heavy or burdensome.

Nature Walk:Waterfalls, Bamboo Forests and Spiders

Our morning plans are disrupted by Mother Nature. Showers are in the forecast for most of the day. Undaunted, we set out to do some, not all, of our planned hiking. Umbrella in hand, a bit of water won’t be a problem. After all, this lush green vegetation and rushing streams result from lots of rainfall.

Odaki and Medaki Waterfalls

Just a short ride from Tsumago, one finds a long staircase and short path leading down to raging twin waterfalls. The setting is serene, surrounded by forest, mossy trees and rocks, and rushing mountain streams. I appreciate that the day is cloudy and cool.

The Odaki and Medaki waterfalls are a pair of companion falls in the Kiso Valley. Their names carry symbolic meaning: Odaki means Male Waterfall, while Medaki means Female Waterfall. The naming of waterfalls in male and female pairs is common in Japan and reflects ideas of balance, harmony, and the duality of nature.

The two waterfalls flow near one another but fall from slightly different streams of a mountain river. Odaki, the male fall, is taller and more powerful, with a drop of about 60 feet. Medaki is smaller and more graceful looming around 8 feet high, cascading in a gentle narrow stream.

Old Nakasendō Way

For the past three days, we have traveled along this mountain path and through the post towns of Narai and Tsumago along Old Nakasendō Way. This morning, beneath cloudy skies and light showers, we hike a portion of this centuries old trail. Once the path for traders, samurai and shoguns, it now attracts tourist from around the world.

Nakasendō Way was one of five Edo-period highways linking Kyoto and Edo (Tokyo). It passed through Japan’s central mountains, dotted with post towns where travelers rested, traded, and experienced traditional culture along their journey. The shogun’s rules and regulations were very strict as a way of controlling his rivals.

The stretch between Tsumago and Magome is the most famous part of the preserved Nakasendō trail. The path winds for about five miles through forested hills, rustic hamlets, and terraced fields. Stone paths, tea houses, and wooden signposts evoke the Edo-era atmosphere.

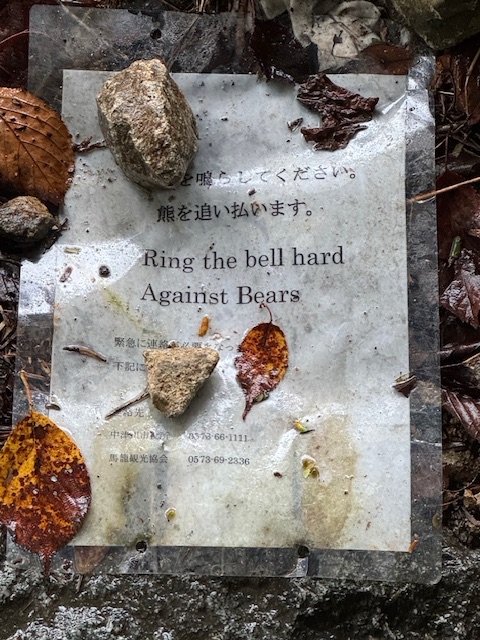

Because of rain, we avoid the steep one mile uphill climb to the waterfalls. Instead, after visiting Odaki and Medaki, we cross the highway to begin the gentle 2-mile descent into the post town of Megome. At the start is an irresistible bell, which seems to announce our entry onto this historic path. Actually, it represents a bell to ward off bears, or possibly attract them that a new meal has entered the trail.

Along the way, we pass waterfalls, streams, and viewpoints of the Kiso Valley. Low clouds drift over the peaks to interfere with views but add their own mystique. This is a moderately easy hike, rewarding with quiet scenery, traditional villages, and a sense of walking back in time.

The path is peaceful (except for us), uncrowded (except for us) and carves its way through a tall cedar and bamboo forest. Sounds of rushing water remain a constant reminder of the amounts of rain that fall in these mountains. It also explains why eyerything appears lush and green. The occasional large waterwheel freely operates along these waterways.

The cedars here are Japanese cedars (sugi), many planted during the Edo period to shade and protect travelers on the old highway. Mature trees typically reach 100–130 feet, and their straight trunks rise high with only a narrow crown of branches at the top, giving the paths a solemn, cathedral-like atmosphere.

The straight, towering trunks soar upward, creating a natural colonnade that filters the light into long shafts. The air is cool, still, and faintly resinous, and the path beneath is often shaded, giving the impression of walking through a quiet, green cathedral.

The dense bamboo groves are smaller in scale but equally striking. Common species in this region grow to around 30–50 feet. The culms are slender compared to the massive cedars, and they crowd closely together, creating a soft rustling sound in the wind and an almost enclosed green tunnel for walkers.

Trichonephila clavata

Every quiet branch plays host to a huge spiderweb occupied by a large yellow lady. These large yellow spiders are Jorō spiders (Trichonephila clavata). They are common throughout Japan in late summer and autumn, especially in forests, fields, and near trails.

These female Jorō is striking, with bright yellow bands mixed with black, and often red or bluish markings on their long legs and abdomen. Females are much larger than males, with bodies reaching over in inch and legs spanning 3-4 inches across. Males are small and brownish, often barely noticed. Personally, she reminds me of the Black Widow and her tiny male mate, which she kills after sex.

Jorō spiders weave big, strong orb webs between trees and shrubs, sometimes stretching across paths. I saw them everywhere but thankfully did not walk into her web. (Imagine loud screaming and twisting here) They are harmless to humans, not aggressive, and their venom is only effective on small insects. Locally, they’re even admired for their vivid patterns, though hikers sometimes find their huge webs startling when walking into them on narrow trails.

They’re especially visible in autumn because this is the peak season of the Jorō spider’s life cycle. By September, the females have reached their maximum size, with vivid yellow-and-black coloring that stands out against branches and leaves. At this stage, they build large orb webs—sometimes over a three feet wide—across open spaces in forests, paths, and gardens. The webs are designed to catch more prey before winter. Males, being tiny and brown, mostly linger near the webs of females for mating.

In Japanese folklore, the Jorō spider is tied to both wonder and caution. Its name itself, Jorō-gumo (絡新婦), literally means entangling bride or binding woman, and over time it became associated with a famous yokai (a supernatural creature).

The legend says that a beautiful woman might appear to a wandering traveler, inviting him to rest. Once he lets his guard down, she reveals her true form as a giant spider and ensnares him in her web. Stories vary — sometimes she devours the victim, sometimes she drains his spirit, and in some versions she even keeps men captive forever. Because of this, Jorō-gumo became a symbol of seduction, entrapment, and hidden danger.

For me, she still seems like a Black Widow in disguise.

Magome-julu

I arrive into the beautiful Edo post town of Magome. At about 2,000 feet, the air feels nippy but refreshing. Mostly, showers have stopped. A stone-paved street winds through town, still lined with dark wooden inns, old teahouses, and little shops selling sweets and bamboo crafts. I don’t think the residents will ever run short of bamboo here.

A small gurgling koi pond and the sound of water wheels turning along the path breaks the silence. Mist lingers in the valley, obscuring the view of the mountains that frame the town, but the entire scene feels like a painting.

Walking slowly down the slope, I pause at lookouts where rooftops cascade down the hillside with Kiso Valley spreading out below. No shopping for me but I enjoy a leisurely stroll downhill to Hillbilly Coffee for a refreshing, and warming, coffee latte. Watching the hikers and tourists pass by, Magome still feels like a post town—a place of rest and preparation for travelers trekking their long journey through the mountains.

Rocking and Rolling Thru the Mountains

We continue traveling by bus north into the higher realms of Japan. Scenery is spectacular. Mountain peaks rise higher, air is crisper, roads are narrow. Peaks here rise over 5,000 feet Villages and towns line the way. We weave and twist our way for about two hours to Takayama.

I think an unexpected surprise about Japan was how mountainous, and forested, it is. One hears everything about the 12,389-foot Mount Fuji. I read little about all the other peaks. Notable peaks include Kita at 10,475 ft, and Okuhotaka rising 10,465 ft. Mount Fuji may be the most famous, but Japan boasts 14 other peaks above 10,000 feet. There exist another 29 peaks over 9,000 feet.

Mount Fuji is not the only volcano in Japan. This country has over 100 active volcanoes. While the last volcanic eruption was in 1707, that is not the case when it comes to earthquakes. Japan experiences as average of 85 earth shakers a month. On average an earthquake will hit near Japan roughly every 8 hours.

As a Californian, I am unconcerned as we experience thousands each year – at least 500 shake hard enough to be felt. However, the main difference between our two locations is Japan tends to experience more quakes above a magnitude 4!

Oh, I won’t dwell on typhoons. Three to four typhoons strike Japan’s shores every year with sustained winds over 74 mph. September is peak month. Hopefully, Mother Nature is aware of that weather statistic.

Lodging in Takayama

I look forward to our stay at the Tokyu Stay Takayama Musubinoyu as it involves 2 whole nights in the same room and bed. While still a blend of tradition and hospitality, the hotel borders on the modern in amenities and comfort. My room not only offers a refrigerator but a washer/dryer.

And be still my heart, there is a bed.

In the evening, we dine in the hotel. Every dinner service varies a little but always serves at least a dozen little bits in its own special dish or bowl. Tonight is no different. We each have a brazer where we can grill our own small strips of Hida beef. Not enough food? The buffet is around the corner.

We all wear our samue and dining slippers.

Supposedly, the first bite of Hida beef is like a tiny culinary epiphany with melt-in-your-mouth texture. It comes from Japan’s Gifu Prefecture well south of here and ranks among the country’s finest beef. Raised from black-haired Japanese cattle under strict standards, Japan celebrates the meat for its rich marbling, tender texture, and deep, savory flavor. While Kobe beef may be better known, Hida is pretty good. However, beef, no matter the color of cow, depends on the chef. And my chef, Me, earned my points. The brazer-cooked beef was delicious.

Unfortunately, there is no alcohol sold outside the dining room. On the ninth floor one can find a relaxing area, balcony and wonderful views over Takayama. The train station lies below us. From here, all looks modern.

I find an alcove with the ubiquitous vending machine. Insert some Yen, push a button, and out drops a cold can of Asahi Super Dry.

All is good.