30 September 2025

After a delightful evening in Narai followed by a Western breakfast, I enjoy time to wander Narai’s streets. The village seems a good place to buy lacquerware and woodcrafts. Not being a shopper, I stroll main street to enjoy the wonderful architecture. Perhaps I’ll spot a keychain with a Godzilla on it.

Narai-juku – Beyond the Lacquerware

The entire main street, Old Nakasendō Way, is little more than a mile, hardly long enough for me to earn my steps for the day. It appears impossible to get lost. Along the way are several interesting stops.

Historic landmarks include temples, a local history museum, shrines and the Tezuka Family Residence/Kamitoiya Museum. The home represents a beautifully preserved Edo-period merchant’s house which once served as a key wholesaler and logistical center on the Nakasendō Way. A variety of craft shops open around 10.

Jizō Statues

At one end of Nakasendō, across from the train staton, there exists a small side road to the left. Up that lane, about a block, on the left, are some wide stone stairs. A quiet shaded pathway leads to Nihyaku Jizoson.

In front of a small shrine, under tall cedar trees, you find around 200 small, stone Jizō statues shaped like children or depictions of Buddha. Collected during the Meiji era when modern infrastructure threatened their original locations, these figures were positioned here as a cluster of quiet guardians.

Jizō Bosatsu, known as Ojizō-sama in Japan, is a beloved Buddhist figure—a bodhisattva who delayed enlightenment to help others. He’s revered especially as the guardian of children and travelers. People often dress Jizō statues in red bibs and caps as symbols of protection and comfort.

Gyokuryuzan Chōsenji Temple

Referred to as the dragon temple because the ceiling of the main hall features an elaborate 65-foot dragon painting, created by a Hida craftsman during the Meiji era. The dragon is said to protect monks and watch over visitors. It is sometimes called a roaring dragon (because of the echo effect when clapping inside the hall), though visitors are now asked not to clap to preserve the structure.

Chōsenji belongs to the Sōtō Zen sect, one of the two major Zen schools in Japan (the other being Rinzai). The Sōtō sect emphasizes seated meditation. During the Edo period, Chōsenji functioned as a lodging point for the tea jar procession in which tea leaves were transported along the Nakasendō Way.

The temple grounds hold the graves of notable individuals. There are also several stone carvings and an excellent Jizō statue. To the right of the entrance is a small Buddhist cemetery.

Stop in at a Cemetery

There are several large and small cemeteries of various sects in Narai. A few minutes of exploration reveals insight into the family burial practices.

Japanese Vending Machines

Not all is ancient wood and history in Japan. Even here, along this old trail sit the ubiquitous vending machines, possibly the country’s most charming obsession with convenience! You can’t walk more than a block without spotting one, often glowing like a beacon of caffeine and curiosity on a quiet street corner. There are well over 4 million machines across Japan, making them more common as manhole covers. Vending machines can even withstand earthquakes, power outages, and emergencies, and they provide free access when such events happen.

What makes them so great is their sheer variety. It doesn’t stop with hot and cold drinks. I’ve stumbled upon vending machines selling umbrellas, ties, corn soup, and ramen. They’re spotless, reliable, and open 24/7. In a land where politeness reigns, the vending machine might be Japan’s ultimate host: never intrusive and always convenient.

Thru Kiso Valley

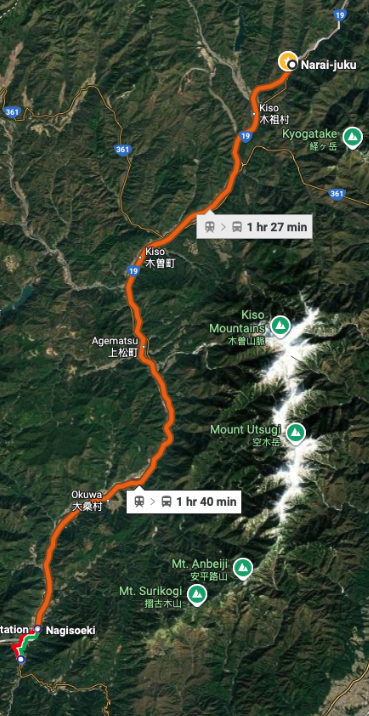

We depart Narai via a Local JR train for our continued journey through the gorgeous mountains of Kiso Valley.

Mountains rise steeply on both sides, with peaks that often top 6,500–8,500 feet. They’re part of the Central Alps, so the terrain feels dramatic—tall ridges, deep gorges, and dense cedar forests that once supplied timber for castle and shrine construction across Japan.

Because the valley floor is narrow and shaded in places, farming has always been a challenge. Still, locals grow buckwheat (for soba noodles, a regional specialty), rice in small paddies, plus vegetables like daikon radish and leafy greens. You’ll also find apples and chestnut orchards, since the cooler mountain climate suits them. Forestry and lacquerware production (using sap tapped from local trees) were historically just as important as crops—helping sustain these post towns along the Nakasendō.

Debarking at the Naglso Station, we board a bus for the remainder of our journey. Our ultimate destination is the village of Tsumago, another of the post-towns on the historic Nakasendō Way.

Not just trees along our route

Exploring Tsumago

Tsumago preserves its Edo-period charm as a post town along the old Nakasendō route. Time seems to have politely stopped and bowed before stepping aside.

Dark wooden houses and rustic inns line the narrow, flat street, their tiled roofs and latticed windows making me feel like I’ve stepped onto the set of a samurai film.

No power lines clutter the sky, few cars are seen, so the atmosphere feels remarkably authentic. Lanterns glow at dusk, the sound of footsteps echo on stone, and the scent of cedar fills the mountain air.

Honored Tree and Horse

The village exudes peace and relaxation. You have to love a town that highlights and respects a big tree. Their Silver Osmanthus Tree blooms around the end of September and its fragrance wafts over most of the village. I hear the fruit makes great jam.

Wandering the streets, there exists many opportunities to taste local delicacies. I spot a tiny stand tucked between old wooden buildings, and there it is: gohei-mochi, skewered on a stick like some ancient samurai snack. Perfectly pounded rice, coated in a glossy miso glaze, it smells like sweet, smoky heaven. One bite and the outside crunch gives way to chewy, comforting rice, and suddenly I understand why travelers along the Nakasendō have been eating these for centuries.

Gohei-mochi is a traditional Japanese snack from the Chubu region, including the Kiso Valley. It consists of pounded rice formed into flat or oval shapes, skewered on sticks, and coated with a savory-sweet miso-based sauce that often includes ingredients like soy sauce, mirin (rice wine), or ground walnuts. Cooks then grill the skewers over an open flame, giving the rice a slightly crispy exterior while keeping the inside soft and chewy.

I remember an unspoken law of Japan: never eat while walking. Beware the hapless tourist who eats their gohei-mochi while waddling down the cobblestone street. Locals may give you the kind of side-eye usually reserved for people who wear socks with sandals (whoops, I do that too!). The trick? Stand still like a samurai on sentry duty. Bite, chew, savor, and don’t even think about walking. And, then order a second or third.

Icons of the Streets

Wara-uma literally means straw horse. Found specifically in the Kiso Valley, they link to the history of post-towns as horses were once integral to travel, transport and messenger service. Displaying a horse figure evokes that history.

Horse figures, made out of rice straw or other straw materials, are considered symbols of fortune. The idea is that they bring safety, good harvests, prosperity, and protection

I see the odd statues of raccoon dogs about the street. Called tanuki, the statues are a mix of folklore and fun, and they carry a very specific symbolism. Tanuki statues are usually placed outside restaurants, shops, or inns as charms to attract customers and bring business success.

Their 8 traits include: wide-brimmed hat, big eyes, saké flask, big belly, promissory note, big tail, large anatomical genitalia and cheerful face. Their last two probably a result of the saké.

There really exists a raccoon dog native to Japan. Nyctereutes procyonoides viverrinu – tanuki. It’s a canid (in the dog family), not related to raccoons. Their iconic statue does not do the actual, beautiful animal justice.

Nagiso Town History Museum

The Nagiso Town History Museum consists of three distinct exhibits. All come together in one compact, easily walkable package. It’s a beautifully layered way to understand why Tsumago isn’t just a charming village, but a preserved piece of living history.

The History houses models, videos, and artifacts tracing the centuries-old story of Nagiso and the broader Kiso region. Displays explain why villages like Tsumago came to be so well preserved. All is in Japanese but our guide explained the significance of the artifacts.

Waki-Honjin Okuya or Hayashi Family Residence, exemplifies late Edo–early Meiji architecture. Rebuilt in 1877 from Japanese hinoki cypress, displays include tools, household items, and literary treasures tied to celebrated writer Toson Shimazaki. A prominent 20th-century Japanese writer, he captured the clash between traditional and modern values during the Meiji Restoration in his realistic fiction.

The third section of the museum complex is the Tsumago Post Town. This building once lodged feudal lords and honored travelers, and builders reconstructed it using late Edo-era floor plans from the Shimazaki family estate. It’s an interesting look into how noble guests would have experienced hospitality centuries ago.

Overnight in Tsumago

Our lodging for the night is outside of the village at Taoya Kisoji. The hot spring ryokan offers tranquil lodging with a blend of traditional Japanese aesthetics and modern comforts.

My tatami room features tatami mats, toilet shoes, yukata for casual lounging and dining, and a private bath. All the amenities a Westerner could want. Except a bed. However, the futons and pillows are very comfortable. But then, I like a solid mattress. One does not present the best of views getting off the floor in the mornings.

Natural onsen bath options include both indoor and outdoor spas, which I hear were wonderful. Still not interested in using the baths.

And for a delicious dining break, the huge buffet-style dining combines Japanese and European cuisines. In fact, it included everything but the kitchen sink. If you can’t find enough good food here, then you are a lost soul indeed.

Not only dozens of sweet and savory offerings, but it is an all you can drink night. Be it saké, beer, wine, vodka, Jack Daniels, or liquors, one may drink up. I take a sipping test of the five saké wines offered, from dry to sweet types. Judgement is: all taste terrible.

I stick with the beer. The Asahi Super Dry is quite good. Sapporo ranks a close second.

Jinsei o tanoshimu (人生を楽しむ). “Enjoy life”

0 Comments