14 December 2025

Over breakfast, we plan how to spend the day among the ruins and legends of Athens. The Parthenon shouts for our return, silent stones rest around every corner, ancient churches pop up unexpectedly, but which site screams the loudest?

National Archaeological Museum

One final archaeological museum? Will this museum say anything new? Why one more?

Because this one isn’t just another archaeological museum — one might say it’s the greatest hits album of ancient Greece, all in one very large, well-lit building. No driving, climbing or weather protection required.

After two weeks of ruins, temples, and regional museums, the National Archaeological Museum in Athens does things that others simply don’t:

It connects the dots. We’ve seen fragments in situ — a statue here, a mosaic there, a story half-told in Delphi, Olympia, Mycenae. This museum pulls those pieces together. What might feel like repetition, just more pottery shards, becomes summarized history: how styles evolved, how gods changed faces, how power, beauty, and belief shifted over centuries.

We meet the originals. These aren’t representative examples or copies. These are the real deals. Bronzes like the 5th century BCE Artemision Zeus (or Poseidon), arm raised mid-throw, muscles taut; proud Emperor Augustus who feels uncannily alert; or the Antikythera Youth 340–330 BCE, eyes inland, calm face — it feels like someone thinking, not posing. A perfect counterpoint to Zeus.

A favorite – The Jockey of Artemision circa 140 BCE, a beautiful bronze of a young boy clinging to a galloping horse. The horse’s veins, the boy’s eyes wide, the horse literally flying through the air.

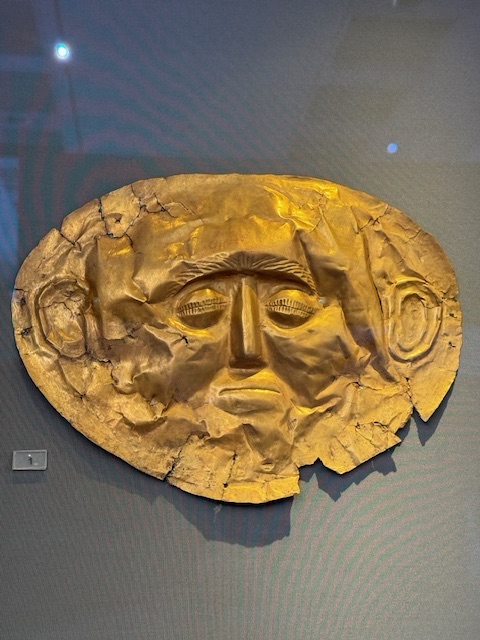

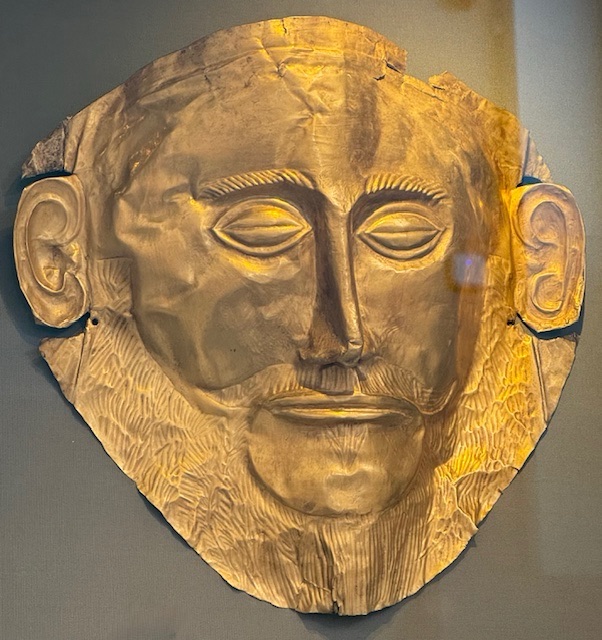

And a star of the museum – the Mask of Agamemnon (yes, that one), is prominently on display as we enter the museum. No searching for the gold. Agamemnon’s golden mask, along with pounds and pounds of finely crafted gold artifacts are on display.

The Telegram from Heinrich Schliemann to King George I

November 16/28, 1876

(originally written in Greek)

Your Majesty, it is with great pleasure that I inform you that I have discovered the tombs which, according to Pausanias’ account, belong to Agamemnon, Cassandra and their comrades who were murdered by Clytaemnestra and her paramour, Aegisthus, during a feast. The tombs are enclosed within a double stone circle, something which would only have been erected in honour of exalted personages. Inside the tombs, I have discovered fabulous treasures and ancient objects of solid gold. These treasures alone are enough to fill a large museum which will become the most famous in the world and will attract myriads of foreigners to Greece from every land. Since I work out of sheer love of science, I naturally make no claim on these treasures and enthusiastically make them over, in their entirety, to Greece. May these treasures be the fondation of immeasurable natonal wealth.

Just a fraction of gold funeral masks and artifacts found in Mycenae. Had Lord Elgin been as honorable.

But, It’s Really Not Agamemnon’s Mask

Discovered by Heinrich Schliemann in 1876 at Mycenae, he declared it the face of Agamemnon. We now know it’s about 300 years older. Traditionally, Agamemnon is associated with the period of the legendary Trojan War, typically dated to the 13th century BCE, but the Mask of Agamemnon was created centuries earlier, around 1550–1500 BCE. Regardless, one is looking at a moment when myth, ego, archaeology, and wishful thinking collided.

It’s unsettlingly human. Unlike idealized classical faces, this mask has importance: heavy lids, a mustache, an authority, the face of a man who ruled and was feared. It speaks of Mycenae and a civilization of elites who buried their dead with gold pressed directly onto their faces. Just gold, thin as paper, carrying 3,500 years of ambition.

This museum represents a grand finale to the Greek story. We walked around a lot of rocks, columns and foundations during the past two weeks. The artifacts within this museum fills in the details. Pottery, sculpture, tools, jewelry and items of everyday life bring Greek history alive.

Zigzagging Crowds, Contented Cats, and One Pastry Shop

Athens is crowded. Compared to the days spent in the Peloponnese, Athens is a megalopolis crammed to the mythical sardine level of packing.

Today is sunny but cool. Over 650,000 people live in Athens proper and it seems they all crowd into the Plaka and onto Athen’s streets. Athenians enjoying their Sunday Volta —music blasting, shoppers, voices overlapping, the steady zigzag of bodies.

We threaded our way through the crowds to lunch, where service came slowly, as it does here. But, the food arrived, delicious and satisfying, the kind that rewards patience and reminds you that Greek meals are prepared, not rushed.

Afterward, we split off, each drawn in different directions. I circled the Ancient Agora, where history hums quietly beneath the noise of modern life. Cafés spilled into the streets, chairs turned toward the sun, and cats lay stretched and unbothered, as if they alone understood the correct pace of things. Eventually, GPS became my thread back through the maze to Syntagma, guiding me toward familiar streets and the comfort of knowing where I was again.

The Silence of Stones

Wherever I walk, I am surrounded by an ancient history of stones. I suspect Athenians get used to these views, but as a visitor, I am not. Everywhere stones tell a story. The cats seem to know. It takes me longer.

Horologion of Andronikos Cyrrhestes, or Tower of the Winds, is a 1st-century BCE marble octagonal tower found in the Roman Agora. It served as an ancient weather station and clock.

The tower featured wind gods on each side, sundials, a water clock, and a rotating bronze wind vane, helping Athenians track time and weather.

Panagía Kapnikaréa Church, tucked into busy Ermou Street, is a quiet 11th-century Byzantine gem. Despite modern crowds rushing past, its cross-in-square design, brickwork, and faded frescoes offer a moment of calm, linking present-day Athens with its deeply layered Christian past.

In its courtyard, the statue of Constantine XI Palaiologos, the last Byzantine emperor, who died defending Constantinople in 1453. He’s often mistaken for Constantine the Great, but this figure symbolizes the end of Byzantium, standing quietly amid modern Athens.

And above it all looms the Acropolis. What a sight this would all have been a century or two before tall buildings and noisy streets.

And One Bakery Stop

A stop at El Greco was non-negotiable. Two of these, two of those, one of that—pointing, smiling, surrendering to temptation.

Arms loaded with pastries, I made my way back to the Hotel Niki Athens, while visions of sugar-calories of delight danced in my head.

Athens: Where a City Spills Into the Streets

A last evening amid the flow of lively, hustling Athenians. Choosing a restaurant: Mezze Athens. Getting a table, heaters above to take the chill off the night.

Ordering a light meal of grilled octopus and stuffed squid with yellow split pea dip. (Those pastries did take the edge off my appetite.)

Always a white wine. Tonight, the chilled white nectar of grapes comes from Meteora’s heights—a cool blessing poured to complement our meal. A sweet custard dessert complements of the house.

Athens exhales, the city’s pulse slows,

Crowds have faded, their laughter spent,

Songs of philosophers and gods long gone.

The Acropolis watches, timeless, over all.

Tomorrow – preparation for packing, train ride to the airport, and departure from this wonderful Greek life.

And Athen’s streets once again belong to the Acropolis foxes, street cats, and locals.

0 Comments