2 April 2016

Plaza Mayor, Segovia

Gusts have decreased from howling to just brisk as we flee Zaragoza. I’m afraid the winds have done their damage as Gabrielle has struck this city from her places to revisit. Sadly, so have I. Though weather is crisp, dry and sunny, winds associated with the term “anticyclone” distract from our enjoyment. We pack up, drive our little Polo up the rat hole, use the Gabrielle Positioning System to exit town, and we are on our way to Segovia.

“Bet that train looks a whole lot better now,” mi sobrina inteligente says to me. After the struggle of exiting the rat hole garage, I agree with her.

Segovia is located about 200 miles southeast on the plains of Old Castile and is part of the autonomous region of Castile y León. Our rural drive is through small towns, the ubiquitous ancient church built atop the highest hill, buildings of brick and plaster, long rock walls. Some fortification walls remain while occasionally I spot a fortress atop a precipice. True España? There is snow around us. Elevation is 3297′ and the tallest peak is 7972 ft; winters dip to 8° with summer temps of 100°. Glad I kept my sweater and bought a pashmina in Madrid.

Under the Romans and Arabs, the city was called Segovia, “Victorious city”. The first settlers were Celtic before control passed into the hands of the Romans. The city may have been abandoned after the Islamic invasion in the 700s, but by the mid-11th century El Cid and the Castilian army were chasing the Muslims from the north and Christians returned. Positioned along important trading routes, Segovia thrived. So did its gothic architecture. Isabel I was crowned Queen of Castile in Segovia in 1474. In 1985, the old city and its Aqueduct were recognized by UNESCO.

Avoiding seasons of extreme cold or heat, there is much to see in Segovia.

The Roman Aqueducts are remarkable. Located along the Plaza del Azoguejo, the massive arches are a defining feature of the city. Dating from the late 1st or early 2nd century AD, the series of 170 continuous arches undoubtedly are the most important Roman civil engineering work in Spain. The arches run for a mile and consist of about 25,000 mortar-less granite blocks. The highest arch is 95′ before dwindling to just a couple feet at the end of the span. There, I can see the narrow channel through which the fresh mountain water came to the city. At the foot of the highest section of arch, near the plaza, is the Loba Capitolina, Rome’s She Wolf suckling Romulus and Remus.

The Roman Aqueducts are remarkable. Located along the Plaza del Azoguejo, the massive arches are a defining feature of the city. Dating from the late 1st or early 2nd century AD, the series of 170 continuous arches undoubtedly are the most important Roman civil engineering work in Spain. The arches run for a mile and consist of about 25,000 mortar-less granite blocks. The highest arch is 95′ before dwindling to just a couple feet at the end of the span. There, I can see the narrow channel through which the fresh mountain water came to the city. At the foot of the highest section of arch, near the plaza, is the Loba Capitolina, Rome’s She Wolf suckling Romulus and Remus.

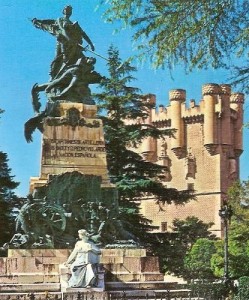

The Alcázar (Royal Palace) was built high upon a stone peninsula between rivers and commands the approaches below. It was first documented in 1122, although it may have existed earlier. A favorite residence of the Castile kings, it was built in a mix of Romanesque, Gothic and Mudéjar styles. The palace is built around two courtyards and has two towers and a keep. The rooms are plainly decorated but the ceilings, frescos, tapestries, paintings and views are worth some time. There is also an artillery museum with a good collection of armor. The Monarch’s Room can challenge one’s knowledge of Castile kings and queens. The Alcázar was a favorite residence of Alfonso X the Wise, probably for the views.

Heroes of Dos de Mayo of 1808

with Alcázar in back.

In front of the Alcázar is the monument to the Heroes of Dos de Mayo of 1808. It commentates the rebellion by citizens of Madrid against occupation by French troops, provoking a brutal repression by Napoleon’s Imperial Troops and beginning a wide-scale Peninsular War.

Madrid had been under the occupation of Napoleon’s army since 23 March 1808, King Charles IV was forced to abdicate in favor of his son Fernando VII, and the French treatment of the royal family and attempts to send the young children to France led to hours of street fighting harshly suppressed by French troops. The uprising in Madrid, together with the subsequent proclamation of Napoleon’s brother Joseph as King, provoked resistance across Spain.

On 2 May a crowd gathered at Madrid’s Royal Palace. French artillery opened fire. Fighting ensued between the poorly armed population and French troops. The French regained control but many hundreds of citizens died in the streets. Most Spanish troops were confined to barracks and the few who disobeyed died as heroes, overpowered by superior numbers.

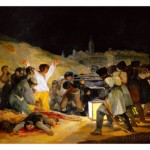

Goya’s The Third of May

The repression following the rebellion was harsh. A military commission on the evening of 2 May, presided over by a General Grouchy, passed death sentences on all of those captured who were bearing weapons of any kind. Hundreds of prisoners were executed the following day, a scene captured in a famous painting by Goya, The Third of May 1808. Thus began the Spanish War of Independence from France.

While the French hoped their rapid suppression of the uprising would control Spain, the rebellion actually gave strength to the resistance. Statues to this 2nd of May rebellion can be seen throughout Spain. Conversely, Spain seems mum about the Civil War of the 1930s and I saw no statue or mention of its victims (except for Valley of the Fallen, more on that tomorrow).

The Walls of Segovia already existed when Alfonso VI won the city from the Arabs a century ago. Alfonso had the walls enlarged, and also increased its perimeter to about 2 miles, adding eight towers, five gates, and several doors. It is possible to enter the interior of the walls using the San Andrés Door. The wall was built mostly using granite blocks but also some recycled gravestones from the old Roman cemetery. The wall encircles the historic quarter and can be walked in several sections and offers some good views. Atop the wall or the Alcázar I gain a perspective of how high the old city sits, gaining vistas of distant snowy mountains and the river and roads below.

The original Romanesque Segovia Cathedral stood opposite the Alcázar and used by the royal armies in defending the Alcázar against the siege of 1521. The rebellious Comuneros waged a Citizens War against the rule of Charles V and were intent on taking the Cathedral to protect its holy relics, and to use its position against the walls of the Alcázar in order to defeat its Royal defenders. After a bitter siege lasting months, the cathedral lay in ruins. Juan Bravo, a leader of the rebel Comuneros who was captured and beheaded, is memorialized with his own statue in a small square in Segovia.

Segovia Cathedral

Charles ordered the Cathedral moved and rebuilt on its present Plaza Mayor site so as to avoid a repetition of destruction from his rebellious community. The massive cathedral was built between 1525-1577 and was the last Gothic cathedral built in Spain. The building’s structure features three tall vaults and an ambulatory, with fine tracery windows, much stained glass, and 20 ornate chapels. Some of the interior decorations were salvaged from the destroyed church. The dome was added around 1630. The Gothic vaults are 108′ high by 164′ wide and 344′ long. The bell tower reaches almost 300′. The stone spire crowning the tower, once the tallest in Spain, dates from 1614 and was erected after a major fire destroyed the original spire built of American mahogany.

Directly next to our Hotel Infanta Isabel is the Church San Miguel. This 16th century baroque church replaced the previous one which collapsed in 1532. The site’s biggest claim to fame is that in its galleries on 13 December 1474, Isabel I was proclaimed Queen.

In 1985 the old city of Segovia and its Aqueduct were declared a World Heritage Site and deservedly so. The city contains a plethora of walking streets, historic buildings, an old Jewish Quarter, and wonderful architecture.

Plaza Mayor, where we enjoy views from our Hotel Infanta Isabel balcony, is a center of activity with a gazebo, restaurants and bars. If activities seem a little subdued at 8 pm, just wait until after midnight and things seem to pick up. Thankfully, our balcony doors shut out most of the gaiety still being had at 3am. However, plaza lights remain on until daylight and the clock bells chime every 15 minutes. It’s a wonderful atmosphere and worth a couple days excursion out of Madrid.

0 Comments