A few degrees north of the Equator, we have sailed under modern power for 6000 miles. The Atlantic is smooth with rolling deep-blue 2-3′ swells, clear skies with clouds on the horizon. Temperatures are 85-92º with humidity 60-65%. However, the sun is blasting directly overhead and makes an oppressive heat – and this is the dry season.

Benin is the size of Louisiana with a population of about 9 million, mostly living on its small southern coastline on the Bight of Benin. It is a tropical, sub-Saharan nation, highly dependent on agriculture. The official language is French. Roman Catholicism flourishes alongside a strong faith in the power of Voodoo. From the 17th – 19th century, the Kingdom of Dahomey ruled current-day Benin. It became known as the Slave Coast due to the trans-Atlantic slave trade. In 1892, France took over the area and renamed it French Dahomey.

Dahomey gained full independence from France in 1960, bringing in democracy for the next 12 years. A self-proclaimed “Marxist-Leninist” dictatorship, People’s Republic of Benin 1972 – 1990, ushered in a period of repression that ultimately led to economic collapse. Formation of the Republic of Benin in 1991 brought multiparty elections.

Beninese dancers welcome us with music and gyrations. Their energy and enthusiasm are a good way to begin our day in Cotonou (the mouth of the river of death). That name might warn away a less intrepid traveler.

Guide Remi Seglonou is back and we are soon driving the streets of Cotonou. Street is a relative term as most are unpaved or sporting the biggest assortment of potholes imaginable. The driving tactic is to dodge the holes regardless if that takes one into oncoming traffic or off the road. Our bus rattles and shakes, its fan belt loudly whines until third gear, and something freely bangs around in the back. However, the air-conditioning works. Will the bus last the day? Along the way we see what local life. Not just roads are in disrepair. Vehicles are battered – no surprise as drivers border on crazy – so proven by the dents, wrecks, and accidents I see. Less hustle and bustle of markets as seen previously, but most people seem busy at a job no matter how small.

The streets are swarming with countless motorbikes. The official taxi, a Zémidjans, is a motorbike with a driver dressed in a yellow jacket wildly dodging around traffic. There are fewer cars and trucks on the roads but they are bigger and have less to fear and tend to take the right of way. It is not for the faint of heart. Stopped for a traffic light, it resembles a swarm of angry bumblebees attacking their prey. There are thousands of motorbikes buzzing past on all sides and in every direction, in and out of traffic with seemingly no rules. Certainly there are no traffic lanes. Roundabouts appear to be potential death traps. We see taxi passengers carrying their shopping, children, and a mattress. All seem confident they will arrive alive.

I notice many entrepreneurs selling gasoline along the road. Contained in wine bottles or large glass jugs, the gas is smuggled in from Nigeria and sold openly at stands in spite of the government’s attempts to stop sales. Customers like the convenience and cheaper price and are willing to protest in the streets to retain the trade. Cars and bikes stop and with siphon and funnel buy a liter. Works well until one of the jars blows up.

In the manner of the Joads heading for California, we drive an hour to our first destination – Ouidah (“widah”). We are not here because it is the home of Remi our guide. We are here because it is the Voodoo capital of the world. With more than 80% Beninese practicing Voodoo, Quidah is the heart of their religion and the origin of voodoo in the Americas and Caribbean. It is to Quidah that believers pilgrimage from around the world.

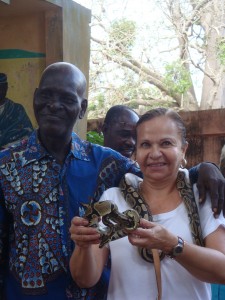

We visit the Temple of the Sacred Pythons and learn of Voodoo traditions, such as scarring the face. Remi emphasizes Voodoo is about respect and honor for ancestors, having power over your life, and increasing power over your environment. Some travelers drape the python over their necks. I can live with myself without this experience. However, I do step into the python house where there are at least 100 pythons. Most are less than 5′ and couldn’t eat anything my size, I hope. They seem to not mind photos, still I would not want to upset them or step on a tail.

The Museum of History, once a Portuguese slave fort, tells of the slave’s life, local history, and voodoo, mostly through pictures. It is small but housed slaves before they marched to the bartering square, then down the Slave Route leading to the Gate of No Return. This red-dirt road is much the same as during the slave trader’s time. The belief is that on death, the spirits of those who left will return. We drive past the Sacred Kpasse Forest before leaving Ouidah. Here voodoo deities live. Perhaps it’s best us naysayers avoid the chief priest and his chickens.

Ganvie, ‘the collectivity of those who found peace at last’, is a village on stilts in Calavi Harbour. Our transportation is a covered taxi boat – motorized but leaking. The Tofinu people lead their daily lives upon the water of Nokoué Lake, their simple homes of wood and tin built upon stilts. The water line from recent floods reaches over a foot into their homes. These are poor people with few amenities. Everything is done on the water in their dugout canoes. Men and women fish, women wearing huge hats for sun protection. There is a floating market, Lovers’ Canal, and little boys peeing into the water from their porches. Over 40,000 live this very challenging lifestyle in what they call the “Venice of Africa.”

We float around the canals with a fair breeze keeping us cool and a leaking boat making the French tourists with their bright orange life vests seem smart. However, the problem is not the shallow water but its brackish quality. The reeds are purposely planted to attract fish but I am not sure if outsiders could eat anything coming out of this water.

Back at the dilapidated pier, we crawl from our leaky boat and are surrounded by children – dirt poor and grasping for a pencil. Will they use them or do they see them as something to sell? I doubt they see the inside of a classroom. Education is neither required nor free. These children lead a simple life but one doomed to poverty. And recent floods worsened the situation with the destruction of classrooms and supplies.

We return to our ship of air-conditioning, flush toilets, clean water, 1000-thread count cotton linens and room service. It will be four days at sea off the coast of western Africa, watching for pirates and crossing the Equator sailing south to Namibia.

P.S. Côte d’Ivoire is on lockdown with all borders sealed after President Gbagbo’s allies rejected election results showing the opposition had won the election. The President’s party has collected all the chads and gone home, so to speak.

0 Comments