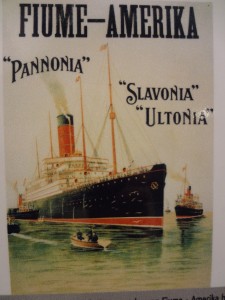

6 June – Rijeka Croatia AKA Fiume to the Italians

I start my day on “my bench” along Lake Bled. Mama duck and her 12 fuzz balls rest along the shore while two lusty swans create waves. They hiss at little helpless ducks yet squeak at each other. The crews are out practicing their rowing. I refrain from more photos of my gorgeous surroundings. Bled is idyllic and I hate to leave but Rijeka beckons – site of the first torpedo factory in the world.

Because of its strategic deep-water port on Kvarner Bay, Rijeka was fiercely contested among Italy, Hungary, and Croatia. Ostrogoths, Byzantines, Lombards, Avars, Franks, Croats, Hungarians, Venetians and French ruled the town before 450 years of the Austrian Habsburgs and a brief Serb attempt to take over. The Kingdom of Hungary encouraged Italian immigration at the detriment of Croats. By 1900, Hungarians had 14 schools in the city, Italians had 26, while Croats had none. No wonder our students from Zagreb refused to visit Italian Trieste. Hard feelings last long in the Balkans.

At the end of World War One, Italian and Croat irregulars occupied Rijeka, both claiming the territory based upon their “unredeemed” ethnic populations. But Italian poet Gabriele D’Annunzio had other ideas. D’Annunzio was a controversial Italian nationalist. Of Dalmatian origins, he was a prominent poet, journalist, novelist, dramatist, and soldier during World War One, controversial due to his influence on the Fascist movement and as a forerunner of Mussolini. D’Annunzio represents an especially colorful chapter in Rijeka history and as good a reason as any to stop in Rijeka. Usurper D’Annunzio slept here – but not for long.

After the start of World War One, D’Annunzio favored Italy’s entry on the side of the Triple Entente (France, G.B., Russia). Having flown with Wilbur Wright in 1908, D’Annunzio volunteered as a fighter pilot, leaving him blind in one eye. Regardless, he took part in daring, if militarily irrelevant, air raids, helping to raise Italian spirits. As commander of the 87th fighter squadron, he organized one of the great colorful feats of the war, leading planes in the “Flight over Vienna” to drop propaganda leaflets on the city.

War strengthened his ultra-nationalist and irredentist views, and he campaigned for Italy to become a European power. Angered by the proposed loss of Fiume (by now with an Italian majority population), at the Paris Peace Conference, on 12 September 1919 he led 2,000 Italian nationalist irregulars to seize the city, forcing withdrawal of Allied (American, British and French) occupying forces, much to the cheers of the local Italian citizenry. Croats not so much.

D’Annunzio desired Italy to annex Fiume, but was denied. Instead, Italy initiated a blockade, demanding surrender. D’Annunzio in turn declared Fiume the independent state of Regency of Carnaro, even drawing up a Constitution similar to the future Italian Fascist system, with himself as Duce. He also tried to form a “League of Nations for oppressed nations of the world ” (like the Italians of Fiume), and to make alliances with various separatist groups throughout the Balkans. D’Annunzio had surprising support, including ships of the Italian Royal Navy, but not of the King, who was somewhat embarrassed by all this falderal. D’Annunzio ignored it all and declared war on Italy, only finally surrendering the city in December 1920 after a bombardment by the Italian navy.

D’Annunzio “retired” to his home in northern Italy but remained a popular figure and a friend of Mussolini. He wrote to Mussolini in 1933 to try to convince him not to take part in the Axis pact with Hitler, even writing a satirical pamphlet about Hitler. In 1944 Mussolini admitted he should have followed his advice.

WWII made the situation uglier. Rijeka was overwhelmingly Italian, but immediately surrounded by Croats and hostile Yugoslavia, setting the stage for an intense and bloody insurgency. Partisan guerrilla attacks were met with Italian and German military retribution. In reprisal when Partisans killed 4 Italian citizens, the Italian military killed 100 men, resettled 800 more to concentration camps. After the surrender of Italy to the Allies, Partisans continued attacks and Germany stepped up oppression. The city was also a target of Anglo-American air attacks that caused hundreds of civilian deaths.

When Yugoslav troops approached in April 1945, one of the fiercest battles in this area of Europe ensued. The Germans inflicted thousands of casualties on the Partisans, but were ultimately forced to retreat. In an act of needless destruction German troops destroyed the harbor and all infrastructure. Attempts to retreat were unsuccessful. Of the 27000 German and other retreating troops, 11000 were killed (many executed after surrendering), while the remaining 16000 were taken prisoner.

The Rab concentration camp, on the Italian-occupied island of Rab just 60 miles south of Rijeka, was one of several Italian concentration camps established during World War Two. It served as the equivalent of a final solution in the ethnic cleansing policy against Slovenes from the Italian-occupied Province of Ljubljana and Croats from Gorski Kotar, in line with Mussolini’s goal stated in nearby Pula, “we can easily sacrifice 500,000 barbaric Slavs for 50,000 Italians.” Commander “don’t shy away from using cruelty” Roatta issued orders for a “complete cleansing” to kill hostages, demolish houses and whole villages, planning to deport all inhabitants of Slovenia and replace them with Italian settlers. (Roatta faced trial for his fascist connection and for abandoning the defense of Rome but never for his participation in ethnic cleansing or his operation of Rab. Ustaše later utilized this camp and others in their ethnic cleansing of the Serbs.)

After the war Rijeka became Yugoslav, decided by the Paris Peace Treaty between Italy and the Allies, and 58,000 of the 66,000 Italians left rather than endure the oppression by Yugoslav Communist authorities. Summary executions of alleged fascists, Italian public servants, military officials and even ordinary civilians (at least 650 Italians were executed immediately after the war) forced most ethnic Italians to abandon Rijeka in order to avoid this type of ethnic cleansing. Probably an excellent idea.

As in the Communist era, no one talks about this – but no one forgets.

My three-hour curvy train ride is thru low mountains and huge expanses of forest, both deciduous and evergreen. One last Passport stamp out of Slovenia and just a “good afternoon” from Croatia. The Croats also turned on the air conditioning. Out of the EU and into a EU-hopeful.

No one would accuse Rijeka of being a must-see destination but it may keep me busy for a couple hours. I have a mission – to sniff out D’Annunzio memorabilia, a daunting task in a city that hates the Italians. Not much seems to have changed since the war; it is a typical port town with Habsburg architecture that could use a serious power wash. The Korzo pedestrian area is blasted with music so loud it could be heard in Italy. It is a stark contrast to other Slav cities as pre-1991 street names remain: Zrtava Fasizma AKA “Victims of Facism,” President Tito Square, and Setaliste XIII Divizije AKA “Promanade of the 13th Partisan Division.”

Tonight I dine at McDonalds – I feel it is appropriate.

7 June – Rijeka

Talked to my host for hints for my D’Annunzio hunt. It is the Fiumare Sea and Maritime Festival and a holiday so limitations exist. He knows of no significant D’Annunzio sites but suggests a couple bookstores. I did read D’Annunzio used the former Governor’s Palace during his 16 months of rule. Every day began with D’Annunzio reading manifestos or poetry from his balcony and would end with a concert and firework display.

Bought my bus ticket to Trieste. The 50-mile trip takes 2 1/2 hours, crosses borders of Croatia, Slovenia and Italy, and is only twice the cost (65 kuna) of my McDonald’s cheeseburger, fries and coke (29 kuna.)

Morning stroll of the huge Farmer’s Market. From there it is all climbing uphill to find my mission going downhill. Tourist Office said museums don’t take holidays so I guess no one told her all are closed. (If I could read Croatian I would know she also didn’t know what day it is.) Can’t even find a good post card. Post Office, usually open 9 to 7:30, is also closed.

So stalk the town and shoot photos of tired facades and disheveled squares. Building since the war has not been well planned so what once was attractive about Rijeka has now lost its charm. I decide it is too early for a pivo so settle for Coke Zero awaiting a store, post office, anything to open. Why have a holiday if there is nothing to do? My mission is failing. Personally, I am beginning to wish D’Annunzio, whose slogan was ‘Fiume or Death’, had held on.

A good thing – The Republike Hrvatske has free Wifi access throughout Rijeka. After one final, fruitless sweep down the Korzo and up the hill to the museum, I admit defeat, much like D’Annunzio 92 years ago. I find a cafe, order that pivo and connect with the world.

I am destined for Trst, as Slavs call it, Trieste when I cross the border into Italy. I pass beaches then enter mountains as I depart Croatia and enter Slovenia. One would never find a Partisan hidden in this terrain. The border is congested leaving SLO and I must get off the bus, walk thru Croatian Passport Control, and reboard. But our driver makes up time by taking the mountain curves on two wheels. He must be Italian.

0 Comments