5 April 2017

I drive the Ardennes. Miles and miles of stunning emerald green fields, the cherry trees a splash of white, just flowering out. Other trees are still in dormancy and an elegant contrast with the green and the white. Cows graze the fields, white too against the green grass. I drive along ridges, the earth dropping precipitously into what is the Meuse Valley where hundreds of thousands of men have fallen in battle.

I drive the Ardennes. Miles and miles of stunning emerald green fields, the cherry trees a splash of white, just flowering out. Other trees are still in dormancy and an elegant contrast with the green and the white. Cows graze the fields, white too against the green grass. I drive along ridges, the earth dropping precipitously into what is the Meuse Valley where hundreds of thousands of men have fallen in battle.

Quiet, peaceful, hard to believe this is the battleground of Europe and the heart of the horror that was the Battle of the Bulge. Small villages dot the horizon, always a church steeple that can be seen for miles. Fertile farmland for as far as the eye can see. Horses and newborn lambs laze in the fields. Everything is so manicured. It’s spring. Tiny green leaves are budding on the trees.

I drive along the ridges, the Meuse Valley below me. Early morning, the infamous Meuse fog slinks among the trees and gives an unworldly feel to the landscape. I imagine how the soldiers must have hated the damp and cold, the reduced ability to see the enemy, the necessity to climb and overtake these ridges. Thousands died trying to do so.

The roads are narrow, hardly wide enough for two of today’s cars to pass, never designed for tanks. The stone buildings seemingly turn their backs to the street. If I look hard enough I can see the bullet holes left by rifle fire. Occasionally I see a ruined farmhouse, deserted since an artillery shell tore into its roof, its occupants dead or forever displaced.

The hills are once again covered in dense forest. There was a time by 1918 that nary a tree was left standing; forests blown to bits by cannon and shell. Hundreds of thousands of men, tanks, aerial bombs and artillery devastated this region. Insanity laid waste to land and people. As I drive through beautiful emerald farmlands and quiet villages of the Ardennes, it is hard to visualize what this land was like on 16 December 1944 – the day all Hell broke loose.

This tranquil landscape was witness to the ferocious battle known as the Battle of the Bulge. It was a last-ditch German offensive aimed at capturing the Belgian port of Antwerp and winning WWII.

The battle began at 5:30 a.m. when an artillery barrage preceded the advance of the German tanks and armament. The Germans, luckily, hit the weakest part of the Allied defenses. Caught by surprise, the American and British forces fought overwhelming forces and were forced to hastily retreat. The German push became known as a “bulge” in the front lines.

By 3 January 1945, in one of he worst winters known to the area, the Allied counter-offensive began. By the end of the battle, on 28 January, the Germans were pushed back to their original positions on the Siegfried Line. The cost in lives was nearly 250,000 Allied and German casualties. Villages, forests, and lives were in ruins.

Proof of the ferocity of the battle are the many monuments and cemeteries throughout the region. Such sites are dedicated to the Canadians, Australians, Belgians, French, Germans, British and soldiers of the Commonwealth. Today’s serene countryside is dotted with reminders of the fallen.

I’m at the Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery. Here lie the remains of 7,992 of our military dead, most of whom lost their lives during the advance of the U.S. armed forces into Germany. Their headstones are arranged in gentle arcs sweeping across a broad green lawn. An overlook affords an excellent view of the rolling Belgian countryside, once a horrific battlefield where most of these men met their deaths.

I’m at the Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery. Here lie the remains of 7,992 of our military dead, most of whom lost their lives during the advance of the U.S. armed forces into Germany. Their headstones are arranged in gentle arcs sweeping across a broad green lawn. An overlook affords an excellent view of the rolling Belgian countryside, once a horrific battlefield where most of these men met their deaths.

I walk manicured lawns among the perfectly aligned rows of white marble stones to Plot F Row 14 Grave 46 where rests Donald A. Sparacin, killed in action 20 December 1944. Private First Class Donald Sparacin receive the Purple Heart. I left an American flag at his stone and will send photos to his family.

I drive through Elsenborn, the only sector of the American front lines during the Battle of the Bulge where the Germans failed to advance. The battle centered on the Elsenborn Ridge in the Ardennes. Untested troops of the 99th Infantry were in the sector because the Allies thought it was an area unlikely to see battle. This assumption proved drastically wrong. Hitler was in a “do or die” frame of mind and ordered his soldiers to make their way to Antwerp, no matter what. The Battle of Eisenborn Ridge lasted 10 bloody days. All attacks were repelled but with heavy losses.

Soldiers were stretched thin over a 22-mile front and faced a determined German advance. The routes were through Elsenborn, Liège, and Malmedy. I drive the same narrow roads that the Germans used to push west. Hardly wide enough for two small cars to pass, the roads and bridges were totally inadequate for Tiger and Panzer tanks. And part of this desperate advance between Saint-Vith and Malmedy was the Kampfgruppe Peiper, under command of SS-Oberstrumbannführer Jaachim Peiper.

I drive into the heart of the bulging lines as I enter the village of Malmedy and the site of the Malmedy Massacre. A monument stands at the crossroads. On 17 December, Peiper’s Kampfgruppe encountered a convoy of lightly armed vehicles from Battery B, 285th Field Artillery of the 7th Armored Division. Overwhelmed, the Americans surrendered. The captured Americans, along with some other Americans captured earlier (127 men total), were marched into a field near the crossroads.

I drive into the heart of the bulging lines as I enter the village of Malmedy and the site of the Malmedy Massacre. A monument stands at the crossroads. On 17 December, Peiper’s Kampfgruppe encountered a convoy of lightly armed vehicles from Battery B, 285th Field Artillery of the 7th Armored Division. Overwhelmed, the Americans surrendered. The captured Americans, along with some other Americans captured earlier (127 men total), were marched into a field near the crossroads.

Germans guarding the Americans opened fire with machine guns, and then dispatched the wounded with a shot to the head. Some soldiers feigned death while the Germans moved among them shooting survivors. A group of about 30 men escaped or survived. Kampfgruppe Peiper and several others were later tried for war crimes for what became known as the Malmedy Massacre. I leave an American flag, among other’s tributes, at the site.

There is a memorial at the crossroads in Baugnez bearing the names of the murdered soldiers. The “Baugnez 44 Historical Center” which has been built on the site of the actual massacre, is just 100 yards from crossroads. It is an excellent museum detailing the events of the Battle of the Bulge and the Malmedy Massacre. Multitudes of artifacts, maps, videos, and photos tell the history of this area during the war. Excellent audio guides help with the explanation of the displays.

Also in the thick of “the Bulge” was the small village of La Gleize, just 15 winding miles away, via Stavelot. A King Tiger tank left by the Germans sits in the town square at another well-done “December 44 Museum” (owned by same man who developed the “Baugnez 44” museum). Germans occupied the town for over a week until Allies bombed and pushed them out. Little was left of La Gleize.

La Gleize is a perfect overnight stay: a small, quiet village whose history is seen on its streets and in the informative museum. Again, a wealth of artifacts, dioramas, maps, and photos. An outstanding film of the battle theater, much of it actual footage taken by the Germans, brings the war closer to reality. The area is tranquil and welcoming the first blooms sf spring. However, the residents still live with the memory of tanks in their gardens and one can still see the bullet holes in the stone facades.

Anyone who has read some history on WWII will recognize the name of Bastogne, 40 miles south of La Gleize. The Bastogne Barracks welcome visitors and there is a section where they are restoring tanks and other armored vehicles. Here, I can hike the battlefields and visit the site where General McAuliffe responded to a German demand for surrender with one word: “Nuts.”

But the best destination is the Bastogne War Museum, dedicated to the Battle of the Bulge and WWII. Opened in 2014, this modern museum is one of he best such museums in the world. The museum presents numerous interactive displays, reconstructions, artifacts, documents, letters and memorabilia from battle flags and medals to uniforms including that of General Hasso von Manteuffel, commander of the German forces, who donated his uniform to the museum. Three outstanding videos tracing the battle can be viewed, much of it filmed by both Americans and Germans. One cannot visit this educational museum without gaining knowledge of and a feel for the Battle of the Bulge.

Located next the the museum is the Mardasson Memorial. This star-shaped American Liberators Memorial honors American soldiers wounded or killed during the Battle of the Bulge. The names of each state (48 at the time of dedication in 1950) encircles the parapet and from its summit, one can view the forests and fields of battle. Battalion insignia, representing the 76,890 killed and wounded during the fighting, line the walls. Below the memorial is a crypt with altars for Protestant, Catholic and Jewish services.

Located next the the museum is the Mardasson Memorial. This star-shaped American Liberators Memorial honors American soldiers wounded or killed during the Battle of the Bulge. The names of each state (48 at the time of dedication in 1950) encircles the parapet and from its summit, one can view the forests and fields of battle. Battalion insignia, representing the 76,890 killed and wounded during the fighting, line the walls. Below the memorial is a crypt with altars for Protestant, Catholic and Jewish services.

And impossible to miss is the 25-foot-tall sculpture of the famous lip-locked sailor and nurse who became symbolic of the end of the war. It is one of four designed by artist Seward Johnson, taken from the famous LIFE Magazine photograph by Alfred Eisenstaedt on 14 April 1945, V-J Day, as news spread through New York City that World War II had ended.

And impossible to miss is the 25-foot-tall sculpture of the famous lip-locked sailor and nurse who became symbolic of the end of the war. It is one of four designed by artist Seward Johnson, taken from the famous LIFE Magazine photograph by Alfred Eisenstaedt on 14 April 1945, V-J Day, as news spread through New York City that World War II had ended.

The region where the Battle of the Bulge took place is not so extensive in terms of miles, but it is difficult to cover more than the best-known sites in a couple days. Practically every village has some sort of a memorial or museum. Over 600,000 American troops were involved in this battle. Fighting was over in one month at the loss of 19,000 American soldiers, 1,400 British, and an estimated total allied casualties of 110,000 – making it the bloodiest battle for American troops in all of World War II.

German casualties were lower at about 85,000. All Hitler’s determination and invictive was not enough to achieve his ambitions. The Germans simply ran out of fuel and abandoned their superior tanks to the villages and roads. The 1st SS Panzer Division, led by Lieutenant-Colonel Joachim Peiper, had to make their way back to Germany on foot.

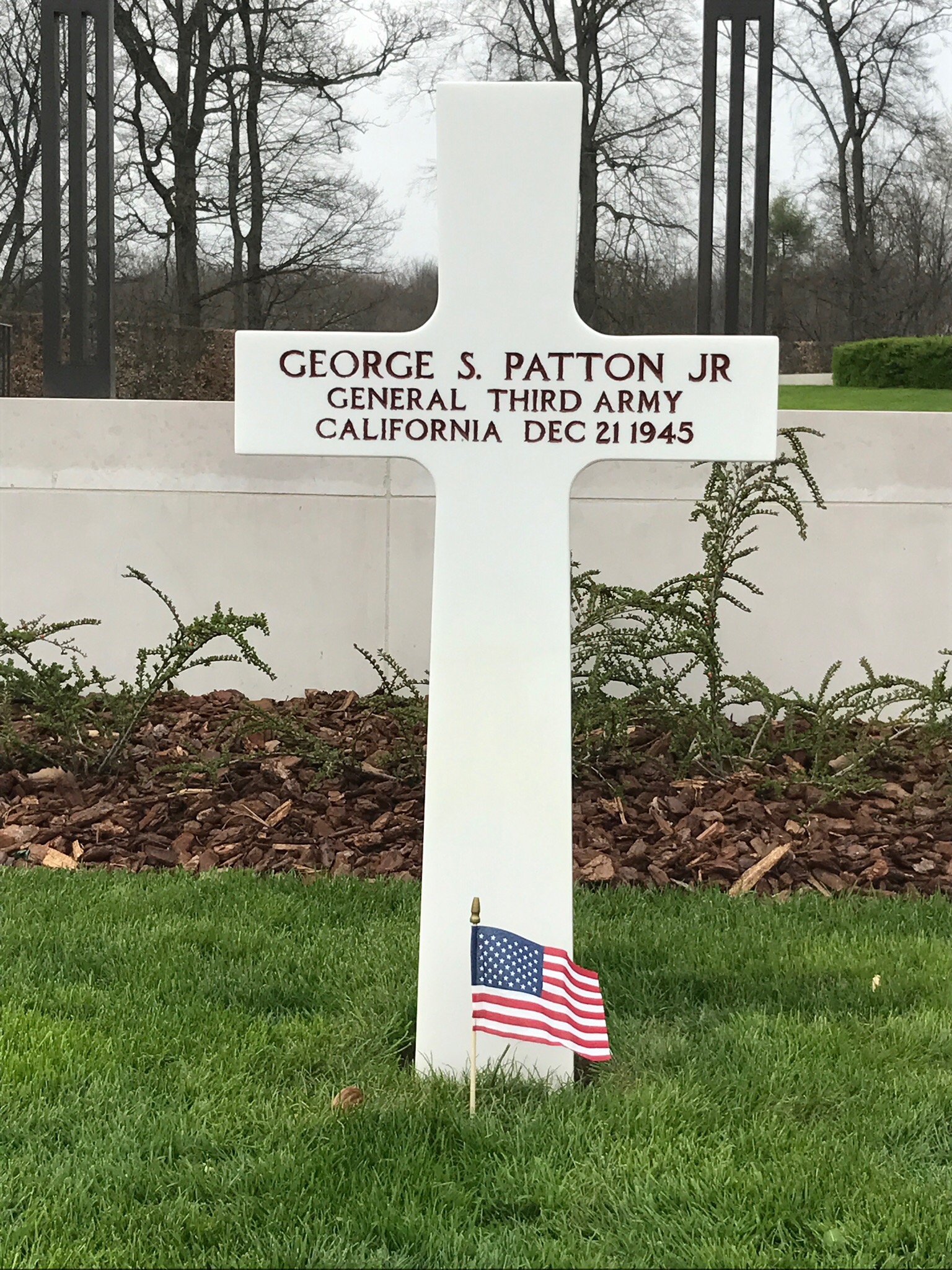

For a final destination in my tour of the Battlefields of the Bulge, I drive further south to the Luxembourg American Cemetery, a 50-acre site, just next to the Luxembourg Airport. The remains of over 5,000 Americans are interred here, including General George Smith Patton, Jr.

General Patton was one of the top military strategists and leaders in history. Like Napoléon, he read the military strategies of Hannibal, Caesar, Alexander the Great, and of Napoléon. German Field Marshal von Rundstedt did not want to face Patton’s troops on any battlefield. The Germans knew Patton’s Third Army was to the south and hoped to make their goal of Antwerp before he could arrive. Von Rundstedt guessed wrong.

General Patton was one of the top military strategists and leaders in history. Like Napoléon, he read the military strategies of Hannibal, Caesar, Alexander the Great, and of Napoléon. German Field Marshal von Rundstedt did not want to face Patton’s troops on any battlefield. The Germans knew Patton’s Third Army was to the south and hoped to make their goal of Antwerp before he could arrive. Von Rundstedt guessed wrong.

General Patton did not die on the battlefield but from injuries suffered in a freak car accident near Heidelberg, Germany on 8 December 1945. He was buried alongside his soldiers. Rumor is his children sprinkled the ashes of his beloved wife of 35 years, Beatrice, on his grave after her death in 1953.

“This is a hell of a way to die,” Patton was quoted as saying.

Indeed, for this greatest of American generals, it was.

0 Comments