25-26-27 January 2018

I leave the north. Flying above Ethiopia, my perspective is of zigging zagging canyons with a sliver of river at the bottom; huge buttes with small villages on top; ridges; endless brown; rocky, volcanic topography – what looks to be an incredibly inhospitable landscape. I see few tilled fields that seem ample enough to feed the population. Wars were fought on this land and woe to the ignorant of its ups and downs, steep escarpments and narrow valleys, and what looks to be a single ribbon of road into the distance. Italian invaders learned the hard way, taking days and back-breaking labor to move their trucks and tanks but a few miles. From up here, I can see why.

I leave the north. Flying above Ethiopia, my perspective is of zigging zagging canyons with a sliver of river at the bottom; huge buttes with small villages on top; ridges; endless brown; rocky, volcanic topography – what looks to be an incredibly inhospitable landscape. I see few tilled fields that seem ample enough to feed the population. Wars were fought on this land and woe to the ignorant of its ups and downs, steep escarpments and narrow valleys, and what looks to be a single ribbon of road into the distance. Italian invaders learned the hard way, taking days and back-breaking labor to move their trucks and tanks but a few miles. From up here, I can see why.

Flying back to Addis, I will escape the “on the ground” experience of Ethiopia’s roads. I am not sad about this. At times, our travel between cities averaged as little as 35 mph and that is on a “good road.” Two-lane roads always have room for more be it trucks, busses, pack animals, tuk tuks, horse and donkey carts, or walkers. Bumpy roads and horn honking are the norm. Bathrooms? Not yet.

We leave Addis quickly to drive south via toll road. It still has cattle crossings with real cattle. The growth of the city is obvious with many new apartment buildings and state housing replacing fields and farmland. A new train line will zip these people into the city for work. The airport is under expansion and modernization. Much of this construction is being done by China.

First stop is Debre Zeit (named by Haile Selassie) AKA Bishoftu (original Oromo name), just 37 miles southeast of Addis. There, I am deposited at a luxurious resort and spa. It is the nicest lodge we have seen and includes massage, face cloths, hair conditioner, coffee, and a patio with wonderful view of Kiroftu Lake. I am to relax for the rest of the day. I imagine this suggestion comes from the knowledge that starting tomorrow, I will not only experience Ethiopia’s roads, but curse them. We are heading into the East African Rift Valley. And using 4X4s.

First stop is Debre Zeit (named by Haile Selassie) AKA Bishoftu (original Oromo name), just 37 miles southeast of Addis. There, I am deposited at a luxurious resort and spa. It is the nicest lodge we have seen and includes massage, face cloths, hair conditioner, coffee, and a patio with wonderful view of Kiroftu Lake. I am to relax for the rest of the day. I imagine this suggestion comes from the knowledge that starting tomorrow, I will not only experience Ethiopia’s roads, but curse them. We are heading into the East African Rift Valley. And using 4X4s.

Examining the Rift Valley via Google Maps, as it wends its way north through Kenya and northeast across Ethiopia to the Red Sea is one thing. Driving through it is quite another. I am challenged to imagine the rift. (Sort of like standing in Santorini and inquiring where the volcano is.) My little gold Google Man is unable to show me anything as he has not traveled these remote regions of Ethiopia.

There are certain landmarks on the globe which everyone must have heard about. The Great Rift Valley has to be one. There is a big welcome sign at the Addis airport that says “The country of origins.” Indeed, all around me is where we humans began. Not so sure about the Ethiopian Orthodox claim that Adam and Eve originated here.

We follow Route 6/TAH4. A rift valley is a lowland region formed by the interaction of Earth’s tectonic plates. A small rift is usually long, narrow and deep while a geologically active area will have longer faults, volcanoes and mountain ranges like I saw in the Simien Mountain area. On Earth, rifts occur at all elevations, from the sea floor (which I will never see) to plateaus and mountain ranges.

We follow Route 6/TAH4. A rift valley is a lowland region formed by the interaction of Earth’s tectonic plates. A small rift is usually long, narrow and deep while a geologically active area will have longer faults, volcanoes and mountain ranges like I saw in the Simien Mountain area. On Earth, rifts occur at all elevations, from the sea floor (which I will never see) to plateaus and mountain ranges.

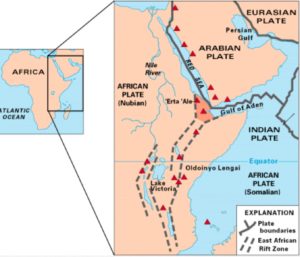

The Great Rift Valley stretches across Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania and is active. Our Earth is pulling apart at the East African Rift (EAR), Earth’s largest seismically active rift system. The EAR is where the Somalian and Nubian tectonic plates are pulling away from the Arabian plate. This activity has been going on for millions of years and, fortunately, will take a lot more millions before people in Addis may have beach front properties.

From space, photos of the Rift Valley are awesome. I can see its path marching across East Africa. In the millenniums past, pressures built causing the two tectonic plates to separate and the center section to drop between two escarpments, forming a valley. This drop of the center creates steep walls. As this process of nature continues, the valley widens, deepening over time as a result of erosion, until it becomes a large basin that fills with sediment from the rift walls and the surrounding area. Rivers flow and lakes form. The EAR is a wonderful example of this process.

The EAR began developing around 22–25 million years ago. At the rate of about 2.5 inches a decade, eventually the Somalian plate will break off, and a new ocean basin will form and Somalia will join Madagascar as an African island. I have stood on or around many of the world’s largest lakes located in rift valleys, including Lake Baikal in Siberia, Lake Superior in North America, and Þingvallavatn, Iceland. Mother Nature is persistent in Her strength but takes Her time.

The USGS map (right) shows splitting along the EAR Zone, its active volcanoes (red triangles) and the Afar Triangle (orange-shaded area). The Afar Triangle is referred to as a triple junction because three plates are pulling away from one another: the Arabian Plate and two parts of the African Plate – the Nubian and Somali.

The USGS map (right) shows splitting along the EAR Zone, its active volcanoes (red triangles) and the Afar Triangle (orange-shaded area). The Afar Triangle is referred to as a triple junction because three plates are pulling away from one another: the Arabian Plate and two parts of the African Plate – the Nubian and Somali.

The EAR is also where Earth’s crust is disclosing its precious secrets in the form of fossils of early human ancestors. Rapid erosion of highlands quickly filled the valley with sediments, creating a favorable environment for the preservation of remains. The rift zone is rich in fossils of the hominid ancestors of modern humans, including 3.2 million-year-old “Lucy” now in an Addis museum. She is the earliest known adult hominid, so far. The bones of several other hominid ancestors of modern humans also have been found here. Richard and Mary Leakey have done significant work in this region. More recently, two other hominid ancestors were discovered: a 10-million-year-old ape called “Choro” found in the Afar rift in eastern Ethiopia (orange-shaded area on the map), and “Naka” who is also 10 million years old.

I travel through this massive depression aboard my very comfortable Toyota Land Cruiser. The road, in most places, is surprisingly smooth and mostly paved. We share the road with the usual mix of people, carts, donkeys, cattle and goats. Commerce is health. The absence of honking is noticeable. We descend a gradual, unimpressive hill to enter the Rift Valley. This is a straight ribbon of road between low, undramatic volcanic peaks. The haze is so bad, visibility is no more than a couple miles. But what is noticeable is the richness of the soil and land compared to that of the north.

I travel through this massive depression aboard my very comfortable Toyota Land Cruiser. The road, in most places, is surprisingly smooth and mostly paved. We share the road with the usual mix of people, carts, donkeys, cattle and goats. Commerce is health. The absence of honking is noticeable. We descend a gradual, unimpressive hill to enter the Rift Valley. This is a straight ribbon of road between low, undramatic volcanic peaks. The haze is so bad, visibility is no more than a couple miles. But what is noticeable is the richness of the soil and land compared to that of the north.

The fields are numerous and green. Sculptured mounds of hay are common, piled high next to the family’s conical hut. Crops include onions, cabbage, lettuce, teff a grain used for making injera, tomatoes, and the wine grapes of Castel Winery (Rift Valley and Acacia). There is also a presence of industry here with immense greenhouses employing thousands in the production of roses (Ethiopia is a world class exporter of roses and flowers), and meat packing facilities where the export mainly goes to Egypt.

Injera, a staple and Ethiopia’s national bread

About teff: Teff is a nutritious, gluten free, high-fiber food and good source of protein, iron, calcium and manganese. It lowers cholesterol and has plenty of lysine and amino acids. To me, when unrolled, it looks like the rippled inside of a cow’s stomach/tripe. Some might compare it to sourdough but injera’s intense yeast/sour mash taste is off-putting. However, this fermented sour bread is consumed as a food staple and the Ethiopian national bread. Injera is shared, eaten by tearing off a piece, scooping up food and putting it directly into your mouth.

There are large herds of longhorn cattle, goats, and camels in the hundreds. And of course the usual donkeys and horses. All these animals look well fed and healthier than their northern cousins. In fact, everything about this region looks richer, with the production of food crops, availability of grass for grazing, and roads for transportation, though animals and carts still have the right of way. Nearby, China is helping to lay a new expressway. I notice there are even sidewalks (though also a lot of road garbage).

The Rift Valley has numerous large lakes that can be more than 140′ deep. Not only are these valuable water sources but an attraction for a number of bird species. We lodged on Kiroftu Lake last night and today walked the shores of Lake Horo and Lake Zeway. Cormorants, grebes, ospreys, ducks, egrets, kingfishers, hammer cocks, fisher gulls, and kites are common. Around Zeway, the marabou stork is in large numbers perched in groups atop trees and lampposts.

Passing several rift valley lakes, we arrive on the western shores of Lake Langano, reaching Sabana Lodge via a bumpy, dusty, rut-filled road. It is a peaceful setting overlooking what is a brown lake. The silt stirs through the water to create its brown coloring. The haze continues and it is not possible to see the opposite shore. I am glad our little caravan of Land Cruisers has arrived safely. Our driver may enjoy zipping his SUV around the pot holes and donkeys a little too much. I may need more alcohol to sustain me over tomorrow’s roads, 188 miles further into the fascinating, changing Rift Valley. Our destination is Arba Minch, the largest town in southern Ethiopia with a population of about 100,000.

Just south of Lake Langano is the growing town of Shashamane. In the 1960s, Emperor Selassie opened Ethiopia’s doors and offered free land to any person who wanted to resettle to Ethiopia. Many Jamaicans accepted the offer. Because the Rastafarians viewed Selassie as their Savior, many moved here to Shashamane, establishing a large community. The presence of Bob Marley’s persona is also more evident here, especially on the tuk tuks.

Just south of Lake Langano is the growing town of Shashamane. In the 1960s, Emperor Selassie opened Ethiopia’s doors and offered free land to any person who wanted to resettle to Ethiopia. Many Jamaicans accepted the offer. Because the Rastafarians viewed Selassie as their Savior, many moved here to Shashamane, establishing a large community. The presence of Bob Marley’s persona is also more evident here, especially on the tuk tuks.

We spend another day dodging cattle, goats, donkeys and people, continuing our journey south through the Rift Valley and into the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People’s Region (SNNPR). Numerous lakes dot the valley floor, providing water to this fertile land. There are vast areas where the only green is the ubiquitous Acacia tree. Enormous sycamores and eucalyptus help to soften the landscape. The main livelihood here is agriculture and livestock, mostly cattle and goats. The ever-present donkey is pulling loads of everything imaginable down the roads. Their drivers seem to be very demanding on these little fellows.

We stop at an Alaba Village. The Alaba people are known for the images they paint on the inside and outside of their huts. They live in family compounds that include the cone-shaped mud huts of several generations (girls live in their husband’s family group). The huts are made of wooden stakes covered with a mixture of clay and dung topped with a thatched roof. For decoration, the family will paint the outside with anything from lions and camels to earthenware pots and herbal plants. The paintings continue on the interior walls.

The hut is quite large and provides for living, cooking, and sleeping quarters for several family members, in this case a family of five. The tall, sturdy center pole braces the thatched roof. About a quarter of the floor space is taken up by livestock as the Alaba do not leave their animals outside at night. The worst predators are hyenas. There is a large storage space above the stable area. The hut is quite spacious and comes equipped with electricity.

The Alaba cook inside, which results in a lot of smoke. The family doesn’t mind the smoke as they believe it deters termites and mosquitoes. There are over 80,000 Alaba in the Rift Valley. The men are very distinctive wearing their tall multi-colored straw hat. The women and children just look dirt poor. As has been the case with children, they know how to hold out their hands and ask “money?”

Driving the relatively straight ribbon of road that is TAH4, I progress through the Rift at a speedy pace. It seems the animals and people in the roads are no reason to slow. I see serious accidents, cars overturned or jackknifed along the side, and I see road kill for the first time. Nothing stops for the wandering donkey or cattle. “Honk” I’m coming through, around or in between. I do not witness Ethiopian drivers stopping for anything, slowing perhaps, but it is vital to keep moving, especially if you are bigger than the other guy. Cow or donkey in the middle of the road? Please don’t move – one step either way and the car will misjudge it’s position and …. Slower traffic like a donkey cart? Honk a warning and zip around it even if driving uphill, around corners, or facing oncoming traffic. There is always room for another lane of traffic. I feel some donkeys are just tempting fate, tired and overworked, perhaps they hope to be put out of their misery. They certainly don’t move!

Driving the relatively straight ribbon of road that is TAH4, I progress through the Rift at a speedy pace. It seems the animals and people in the roads are no reason to slow. I see serious accidents, cars overturned or jackknifed along the side, and I see road kill for the first time. Nothing stops for the wandering donkey or cattle. “Honk” I’m coming through, around or in between. I do not witness Ethiopian drivers stopping for anything, slowing perhaps, but it is vital to keep moving, especially if you are bigger than the other guy. Cow or donkey in the middle of the road? Please don’t move – one step either way and the car will misjudge it’s position and …. Slower traffic like a donkey cart? Honk a warning and zip around it even if driving uphill, around corners, or facing oncoming traffic. There is always room for another lane of traffic. I feel some donkeys are just tempting fate, tired and overworked, perhaps they hope to be put out of their misery. They certainly don’t move!

Paradise Lodge is in Arab Minch atop an escarpment which overlooks immense and dull brown Lake Abaya to the north, equally brown Lake Chamo to the south, and a strip of land called The Bridge of God that divides them. As if this view is not enough, the Bale Mountains rise in the distance to the northeast. However, ever present haze, mostly from dust, obscures all views.

I am told the view will clear with the first rain in April. The resident baboons are nowhere to be seen. Perhaps we both need to come back in the rainy season.

I am told the view will clear with the first rain in April. The resident baboons are nowhere to be seen. Perhaps we both need to come back in the rainy season.

0 Comments