Saxon Villages of Prejmer and Viscri – 24 May 2019

This morning, we motor further into the Transylvania region of Romania. The countryside is peaceful and verdant, the villages quiet with the rustic feel of what I would expect of rural Romania. Mountains surround a flat valley of rich green fields and expanses of bright yellow rapeseed. Rivers of snow trickle down the distant peaks of the Carpathians while sun shines on white storks shopping the farmer’s hay fields for frogs and grasshoppers. There is the occasional man and his herd of cows. Lush, healthy forests of beech and timber march up the hillsides for as far as I can see. This is perhaps some of the most beautiful land in the world where I have driven.

This morning, we motor further into the Transylvania region of Romania. The countryside is peaceful and verdant, the villages quiet with the rustic feel of what I would expect of rural Romania. Mountains surround a flat valley of rich green fields and expanses of bright yellow rapeseed. Rivers of snow trickle down the distant peaks of the Carpathians while sun shines on white storks shopping the farmer’s hay fields for frogs and grasshoppers. There is the occasional man and his herd of cows. Lush, healthy forests of beech and timber march up the hillsides for as far as I can see. This is perhaps some of the most beautiful land in the world where I have driven.

This region of Transylvania continues to reflect the presence of three distinct cultures: Saxon, Romanian and Hungarian. Everything from architecture to food, dress to names reflect the three cultures. In fact, just to confuse the visitor, each town will have a different name for each of the three ethnic groups. For example, we drive to the Romanian city of Prejmer, which the Hungarians call Prázsmár and the Germans refer to as Tartlau. None of which I can pronounce well enough to be understood!

Prejmer

Just 10 miles northeast of Brașov, we stop to explore the former Saxon Fortified Church of Prejmer, the largest fortified church in southeastern Europe and a UNESCO site. One cannot get a concept of its size without an aerial view. Begun by the Teutonic knights in 1212, it was built not only for protection but to last through the ages. The surrounding walls are 40 feet high and over 15 feet thick. Bastions, drawbridges and a secret, subterranean passage were effective in repulsing any invaders. Besieged 50 times, it was captured but once in 1611 by a Prince of Transylvania and then only because the defenders ran out of water.

Just 10 miles northeast of Brașov, we stop to explore the former Saxon Fortified Church of Prejmer, the largest fortified church in southeastern Europe and a UNESCO site. One cannot get a concept of its size without an aerial view. Begun by the Teutonic knights in 1212, it was built not only for protection but to last through the ages. The surrounding walls are 40 feet high and over 15 feet thick. Bastions, drawbridges and a secret, subterranean passage were effective in repulsing any invaders. Besieged 50 times, it was captured but once in 1611 by a Prince of Transylvania and then only because the defenders ran out of water.

Access is via a 100-foot-long arched passage fortified with two rows of gates. Each village family had a designated room for shelter in case of attack. The wall accommodated four stories and 270 storerooms packed with supplies linked by wooden staircases. The defense gallery along the inside walls, reached by a series of wooden stairs and doorways meant for very short people, is about 35 feet up and was the place from which the boiling pitch was dumped onto attackers.

It was from the defense gallery that the infamous “death organ” was used. This machine was made of several weapons that could shoot simultaneously, causing the enemy severe losses. A rotating board on an iron axle with five barrels on each side could be loaded with projectiles. By rotating the axle, the weapon could be continuously fired and reloaded much like a modernist machine gun. Unfortunately, all the pre-planning failed when it came to water.

It was from the defense gallery that the infamous “death organ” was used. This machine was made of several weapons that could shoot simultaneously, causing the enemy severe losses. A rotating board on an iron axle with five barrels on each side could be loaded with projectiles. By rotating the axle, the weapon could be continuously fired and reloaded much like a modernist machine gun. Unfortunately, all the pre-planning failed when it came to water.

This massive red-roofed fortification encircles a Gothic church. The Fortified Church has one central tower and a cross-like floor plan and was built as the Teutonic knights’ place of worship. The nave features late-gothic vaulting. Originally built as a Lutheran church, the interior is quite simple. The intricate vaulted ceiling and organ are very nice as is the triptych altar.

The embattled Knights might have been tempted to open their gates had they smelled the delicious odors of kürtös kalács cooking on open fire right outside the walls. These ‘chimney cakes’ are a pastry rolled onto a large round wooden pin and painted with egg and sugar, grilled, then rolled in walnuts, cinnamon or coconut. Totally delicious as you pull the pastry apart and devour it like ravenous defenders of the realm.

The embattled Knights might have been tempted to open their gates had they smelled the delicious odors of kürtös kalács cooking on open fire right outside the walls. These ‘chimney cakes’ are a pastry rolled onto a large round wooden pin and painted with egg and sugar, grilled, then rolled in walnuts, cinnamon or coconut. Totally delicious as you pull the pastry apart and devour it like ravenous defenders of the realm.

Viscri

Turning northwest, we motor past rocky peaks and though healthy coniferous forests, sure indications of ample water and cold winters. I can almost hear “the children of the night” howling in the thick, dark reaches of the forest. I must remember to look for wreaths of Transylvania’s garlic.

We stop in Viscri. The village and its church is one of a large group of villages with fortified churches throughout Transylvania that form an overall UNESCO World Heritage Site. Located here is one of the most impressive Saxon citadels I have seen. And its view of the idyllic countryside and surrounding mountains is spectacular.

We stop in Viscri. The village and its church is one of a large group of villages with fortified churches throughout Transylvania that form an overall UNESCO World Heritage Site. Located here is one of the most impressive Saxon citadels I have seen. And its view of the idyllic countryside and surrounding mountains is spectacular.

The Saxons, an ethnically German/Luxembourg group, came by invitation sometime after 1141 and built a small chapel. At that time this area was a part of the Kingdom of Hungary. Fortifications of 23-foot high walls were built around the chapel forming an oval and made of river and field stone. Two towers and two projecting bulwarks were added in the 14th century. Tall towers were joined with the exterior walls with an even taller interior central tower. All was conjoined and protected in such a way as to allow free movement and with moveable logs the defenders could shut themselves inside.

The Saxons, an ethnically German/Luxembourg group, came by invitation sometime after 1141 and built a small chapel. At that time this area was a part of the Kingdom of Hungary. Fortifications of 23-foot high walls were built around the chapel forming an oval and made of river and field stone. Two towers and two projecting bulwarks were added in the 14th century. Tall towers were joined with the exterior walls with an even taller interior central tower. All was conjoined and protected in such a way as to allow free movement and with moveable logs the defenders could shut themselves inside.

The whole idea of inviting the Saxons, a hard working and industrious group, was so they could build a defensive wall of fortresses and people with which to repel the constant invasion of the pesky Tartars. (The designation “Mongol” and “Tartar” are often used simultaneously.) The Tatars were a Turkic-speaking people living mainly in Russia. Think Genghis Khan and later Tamerlane, two of history’s greatest generals. Most of Genghis’ army was Slavic. It was Batu, son of Genghis, and his Mongol hoards of skilled horsemen and archers who descended upon this region, and the Hungarian horsemen and Saxon villagers were up to the task but sorely outnumbered. The Transylvanian region survived, as did Hungary’s king, because of the lucky timing of the death of Genghis Khan in 1227. Genghis had several sons and they all rushed home to claim the throne.

The whole idea of inviting the Saxons, a hard working and industrious group, was so they could build a defensive wall of fortresses and people with which to repel the constant invasion of the pesky Tartars. (The designation “Mongol” and “Tartar” are often used simultaneously.) The Tatars were a Turkic-speaking people living mainly in Russia. Think Genghis Khan and later Tamerlane, two of history’s greatest generals. Most of Genghis’ army was Slavic. It was Batu, son of Genghis, and his Mongol hoards of skilled horsemen and archers who descended upon this region, and the Hungarian horsemen and Saxon villagers were up to the task but sorely outnumbered. The Transylvanian region survived, as did Hungary’s king, because of the lucky timing of the death of Genghis Khan in 1227. Genghis had several sons and they all rushed home to claim the throne.

Interesting trivia: Genghis Khan, greatest conqueror the world has ever known, ranks first as having the most children in history, numbering in between 10,000-20,000! The Mongol Empire was the largest contiguous landmass in history and successfully united the numerous nomadic tribes across Northeast Asia. Or his skilled fighters killed them. In fact, some of Batu Khan’s men remained behind to populate what is now the Crimea where DNA links them to Tartars, more similar to Russians than any Asian.

Because of this history of invasion, a series of fortified towns and churches were built across Transylvania. UNESCO has recognized these fortifications for their historic value. Many have been or are being restored. All have magnificent locations and views, as one would expect for fortresses meant to repel invaders. The citadel at Viscri is no exception.

The fortress is a beautiful white stone structure with thick walls and tall towers. The roof is peaked and covered with the standard terra cotta tiling of the times. Interiors consist of wooden staircases, rooms for people and food supplies and ammunition. The entire space is meant to hold a village under siege. If it not for the danger, one would welcome being there just for the magnificent views of the surrounding countryside of green fields, forested mountains and the red tile roofs of the village below.

The fortress is a beautiful white stone structure with thick walls and tall towers. The roof is peaked and covered with the standard terra cotta tiling of the times. Interiors consist of wooden staircases, rooms for people and food supplies and ammunition. The entire space is meant to hold a village under siege. If it not for the danger, one would welcome being there just for the magnificent views of the surrounding countryside of green fields, forested mountains and the red tile roofs of the village below.

The existing chapel was eventually integrated in the 13th century into a beautiful Romanesque church, originally Roman Catholic but switching to Lutheran after the Reformation in the 16th century. Its gallery consists of wooden benches while the apse features a scalloped capital design popular in Germany and unique in Transylvania. Many changes have occurred over the centuries and the church is left with a rather ascetic austerity.

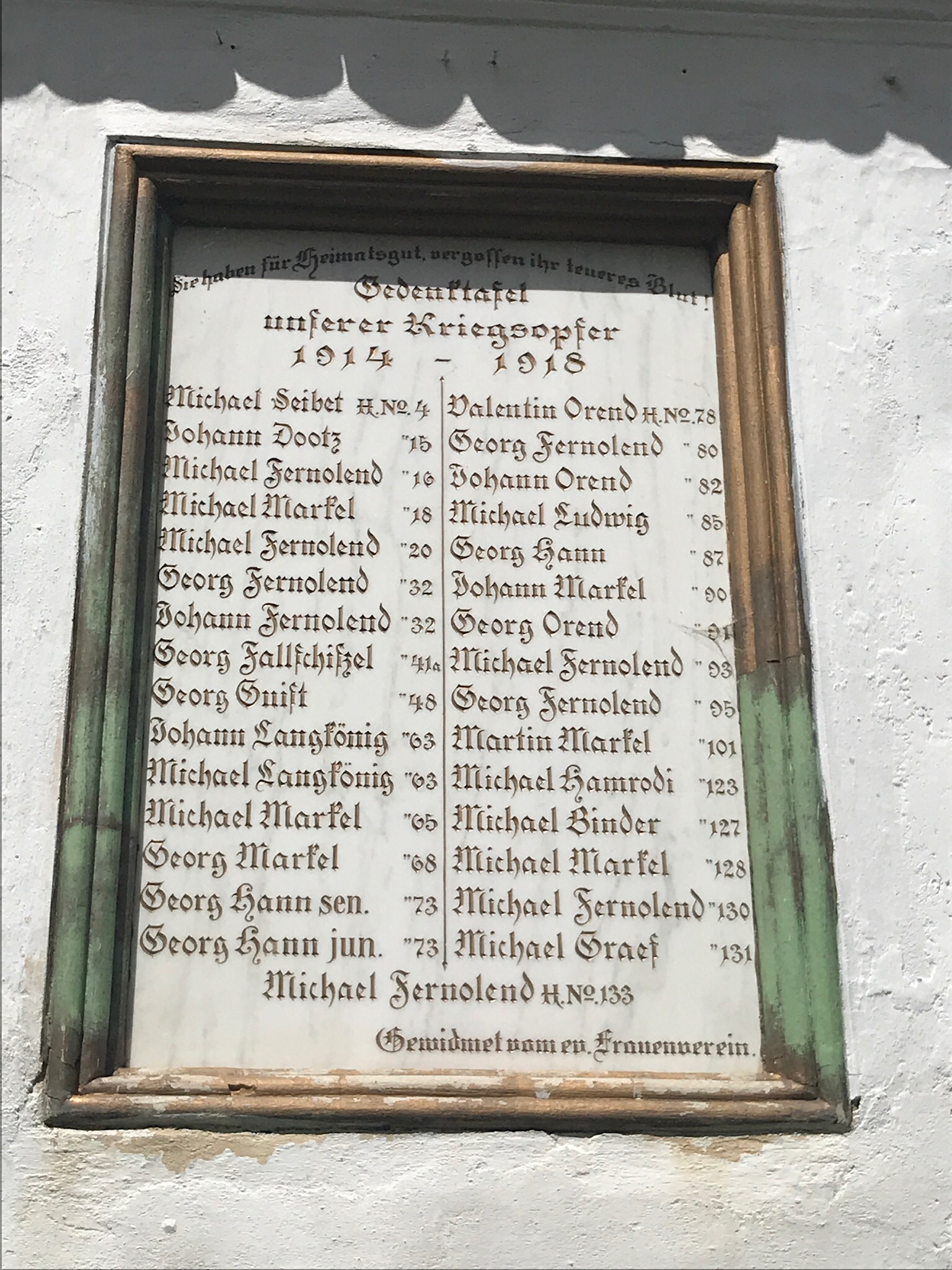

Of interest for these churches is the membership lists that can be seen carved in marble alongside the church. There were so many Saxons with the same family name, the only way to separate them was by following their name with their house number. Some may have acquired a sobriquet because of an abnormality, as in my own genealogy research, there were so many Michaels that one was “Old Michael” another “Creeker Michael” and so on.

Of interest for these churches is the membership lists that can be seen carved in marble alongside the church. There were so many Saxons with the same family name, the only way to separate them was by following their name with their house number. Some may have acquired a sobriquet because of an abnormality, as in my own genealogy research, there were so many Michaels that one was “Old Michael” another “Creeker Michael” and so on.

From the tower, I can see the charming village of Viscri, a typical Saxon Strassendorf with a row of simple houses on either side. Spring water is running into wooden troughs for the horses, excess water creates a stream running down the side of the street. The houses are colorfully painted and retain their original Saxon design. Village life is simple, familial and quiet.

After a wonderful lunch prepared by a local family, we are able to learn more about the village. Across the street, a bright blue house draws our attention. We learn that it is owned by Britain’s Prince Charles. Our host is a prominent leader for the Mihai Eminescu Trust which funds the Whole Village Projects to preserve and restore the buildings and culture of this culturally rich region of Transylvania. From their web page:

After a wonderful lunch prepared by a local family, we are able to learn more about the village. Across the street, a bright blue house draws our attention. We learn that it is owned by Britain’s Prince Charles. Our host is a prominent leader for the Mihai Eminescu Trust which funds the Whole Village Projects to preserve and restore the buildings and culture of this culturally rich region of Transylvania. From their web page:

“During Ceausescu’s dictatorship, the Mihai Eminescu Trust gave dissidents a lifeline to civilisation. And by alerting the West to his plan to bulldoze Romania’s rural architecture it helped save hundreds of towns and villages from destruction. Since then, the Trust has played a prominent role in the country’s academic and cultural revival.

In the post-Communist era, much of Romania’s countryside has come under new threat from agricultural collapse, the abandonment of houses and a lack of awareness of the value of this endangered heritage.

The Trust concentrates on the Saxon villages of Transylvania, a special case because of the age and richness of their culture and the emergency caused by the mass emigration of the Saxon inhabitants to Germany in 1990. These villages – farmers’ houses and barns built around fortified churches, substantially unchanged since the Middle Ages – lie in spectacularly beautiful surroundings. The hills and valleys are rich in wild flowers. Wolves, bears and wild boar roam the mountains and the forests of beech and oak.”

The Prince of Wales first visited in 1997 and since that time has shown a keen interest in the fate of these same Saxon villages which we visit over the next two days. Walking the forests and fields, meeting the people, and learning of the culture and history of the area, the Prince of Wales is now a Patron of the Mihai Eminescu Trust. More information and how you may support this important cause can be found at the Mihai Eminescu Trust web page.

The closest I will ever come to having tea in the garden with a royal is here, peeking through a hole in the gate of Prince Charles.

I understand why Prince Charles and our biologist guide loves this region. We pass through a small village with hay fields and a small lake. Children play in the streets and ride their bikes along the lane. Horse drawn carts carry newly cut hay from the fields. But it is what is sitting atop all the utility poles and house peaks that attract our attention. This village is known as the village of the storks. White storks, white with black wings, return here each year to raise a new batch of offspring. The fields are rich with fat grasshoppers, the lake filled with frogs. We count over 35 nests in less than a half mile. Each nest hosts a pair of storks, who mate for life, and several little storks.

I understand why Prince Charles and our biologist guide loves this region. We pass through a small village with hay fields and a small lake. Children play in the streets and ride their bikes along the lane. Horse drawn carts carry newly cut hay from the fields. But it is what is sitting atop all the utility poles and house peaks that attract our attention. This village is known as the village of the storks. White storks, white with black wings, return here each year to raise a new batch of offspring. The fields are rich with fat grasshoppers, the lake filled with frogs. We count over 35 nests in less than a half mile. Each nest hosts a pair of storks, who mate for life, and several little storks.

We travel north deeper into the Carpathian Mountains to our hotel in the town of Odorheiu Secuiesc, which I will not even attempt to pronounce before a glass of wine or two. Known as Odorhei, the city has been settled since the early 1300s. The population is about 34 thousand, about 96% of which are ethnic Hungarians who refer to this city as “courtyard place.” I hear there are brown bears in the forests and mountains surrounding us. I rather hope for the howling of a wolf, those “children of the night” heard in every Dracula movie ever made.

Alas, all I hear are the neighbor’s dogs.

0 Comments